|

| |||||

War-god under Siege(Rambles of an un-adventurous karā )

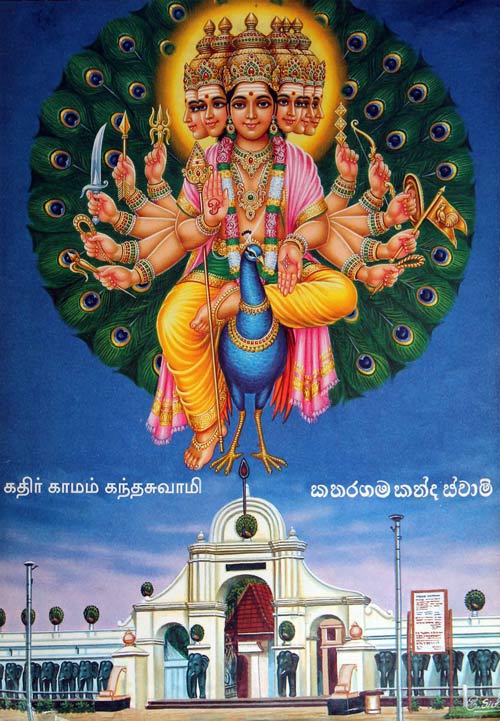

Colombo: The Island of Saturday 16 March 1991Part I"Lord Skanda, the war-god, is under siege, and he doesn't even have a proper jungle at his back for safety.... cchihhh" Breaking off his monologue with an exasperated snap, Swami Chandananda grabs with his hand but misses, and watches helplessly while the little red bead he was trying to thread rolls and bounces down the steeply sloping face of the rock to disappear into the shrubs. "The trouble is that people have forgotten that he is Lord Skanda. The Sinhalese come rushing to do bhara and get something done by Kataragama Deiyyo — it is a kind of disco pilgrimage of the fortune-seekers. And, to the Tamils he is Śrī Murugan or Karttikeya who will help them produce and reproduce." He hands me the joint which he had been trying to smoke while threading a necklace of cheap red beads. Taking a deep drag of the smoke, I settle myself more comfortably on the bare stone and resume my enjoyment of the view from this broad, shaded, stone shelf halfway up the rock outcrop which juts out 150 to 200 feet above the surrounding jungle. "Jungle" is too pretentious a word to describe the pitifully small copse of trees and bushes which surrounds the rock outcrop and, after a hundred yards, makes way for the swathes of green paddy covering the broad plain stretching to the horizon. "Until a few years ago the town had expanded up to the bank of the Menik Ganga leaving the shrine area and the jungle behind it untouched. Now the shrine area has been declared a Sacred Area and has been 'developed'. So there is no more jungle for miles. Only the 'park' and the fields. Except for this bit of trees near Rama Swami's kutiya." Chandananda ties the cord of the bead necklace and holds up the bauble to the light of the setting sun to admire his afternoon's handiwork. Satisfied, he tucks it into his cloth malla and stands up. "Let's go down. I can see Rama Swami coming back with the suddis. I hope they are happy with their tour of the kovil and Kiri Vehera." Following the saffron-robed swami down the slope of the rock I wonder how the two young German travelers had reacted to their first sight of Kataragama's thriving 'bhara' industry. Rama Swami, the doyen of swamis, sits in a corner of his mud hut contemplatively stroking his graying, straggly beard, his silent, diminutive form hardly noticeable in the cool, dark interior of the single large room. While his golaya busies himself in the lean-to kitchen preparing dinner, Elizabeth and Ruth are on a mat outside, chattering in German as they rub insect repellant on their bare arms and legs. Ruth begs me to escort her back to Kataragama to watch the 7 o'clock puja in the Theivani Amman Kovil which Rama Swami has impressed upon them as the sole remaining exclusively Hindu ritual in the ancient shrine. Borrowing Rama Swami's bicycle, I huff and puff my way along the two miles of dusty cart track to the township, my labors compensated by the feel of Ruth's lithe body riding on the crossbar in front of me. They way things have been going between us in the past 48 hours since we arrived in Kataragama, I am delightedly confident of an erotic conclusion sometime tonight. The gaily decorated huts of the kavadi bands have been moved from their site on the high river bank adjoining the bathing place near the footbridge over the Menik Ganga. So we have to leave the bicycle at a kade run by a friend of Chandananda. Although various karās hanging out near the bus stand eye my white female companion speculatively, they know me as a friend of the swamis and therefore refrain from any predatory approach. Sleek Japanese mini-buses continue to race into the square, music blaring and full of fortune-seeking pilgrims. Other metal monsters crouch gleaming in the fluorescent street light as they load returning pilgrims only anxious to get back to reap the benefits of whatever ritual 'deal' they worked out with Kataragama Deiyyo. Clinging to my arm nervously as she is jostled by the crowds, Ruth stares about her in the harsh glare of the flood lighting which today has banished forever the soft, lamp lit twilight under the trees of the shrine area. The crowd is thick and raucous as we push our way along the approach avenue. We have to literally fight our way through the massed bodies at the entrance archway. Everyone except the two of us seems frantically intent on completing as quickly as possible her or his ritual 'deal' with the licentiously generous Kataragama Deiyyo and speeding back to their home towns and 'civilisation'. Dodging a long, snaking queue of pilgrims bearing pooja vatti, we squirm through the press of people all straining to catch sight of the curtain hiding the besieged deiyyo. Several such queues converge at the entrance to the Deiyyo's inner sanctum where nattily shirted Sinhalese lay Kapuralas stand protectively before the screened alter, busy intermediaries for the grasping, salvation-hungry hordes. Entering the gates of the adjoining Theivani Amman Kovil the surrounding walls immediately cut us off from the noise and bustle of Lord Skanda's courtyard. Here we are in an oasis of peace and calm. Only a few Tamil Hindu families and young, newly-married couples are gathered in front of the main shrine room awaiting the pooja. Crossing the white sand of the courtyard, we silently sit on the edge of the mandapa and, within minutes we are in friendly conversation with a vetti-clad, bare bodied Brahmin priest sitting on a mat nearby. Being a North Indian Brahmin doing a spell as chief priest here, he is unable to relate to an eager Ruth the numerous legends about Kataragama and the divine promiscuity of the lascivious war-god. But he is voluble in his despair over the drastic changes overtaking the ancient shrine. "Buddhist monks have by force taken over!" he declares, his white Brahminic ritual thread quivering as his bulging belly heaves in agitation. His bulath-stained teeth gleam through his full beard as he smiles appealingly, arguing his point. "Vivekananda Mission ashram is not! Before, it is only ashram. Now, it is not, you understand? Ashram they take." His broken English is more disjointed as he proceeds with his lament. I nod in affirmation. The Mission ashram, a beautifully designed, Indian-style building, which was once the sole ashram here, was taken over by the state some years ago and made into a museum, I explain to Ruth. What compounds the insult to the Hindus is that the museum is entirely a depiction of the ancient Sinhala Kingdom which ruled over this area and its Buddhist shrine. Of Lord Skanda-Karttikeya, whose sojourn here antedates everything else and who is still the most powerful presence, there is no reference except for a brief mention in a lengthy outline of the Dutugemunu saga. Suddenly the Brahmin breaks off his loud lament and stares at the entrance gates to the kovil. Then he mutters excuses and departs to begin the pooja. Puzzled, I glance casually towards the gate myself and then I look away again, as carefully casual as possible. The two well-built men in civil dress standing just outside the gates have to be policemen. And, in the brightness of the floodlighting, I had seen that they were staring at us. Ruth notices nothing as she is distracted by the ringing of the bells in preparation for the pooja. We get up and I am thankful as we move towards the shrine room and away from the obviously watchful gaze of the cops. And cops they are, I am quite sure. But why this interest in us, is the question agitating my mind as the Brahmin begins his Vedic chant before the goddess. Ruth stands quite still in awe, and her hand clutches mine as the gongs and bells rise in clanging cacophony, but I hardly notice the flickering flames of the lamp as the priest holds it before the divine female. I am busy wondering what the cops are looking for. Are they after me, or the German women, or is it something to do with Swami Chandananda, the "business swami" of Kataragama? Does the swami have some jalbari up his sleeve for the two German travelers? I bend forward to point something to Ruth and quickly steal a glance at the gate. The men are still there. The din of the gongs are louder, the Brahmin's chant now a wail of terror in my ears. Beyond the sounds and lights of the adoring community lie darkness and the threat of the unknown. In the courtyard of the war-god lies danger. by Rasthivadu Part II of "War-god under Siege"

|