|

| ||||||||

Sri Lanka's Mud Culture:

|

|

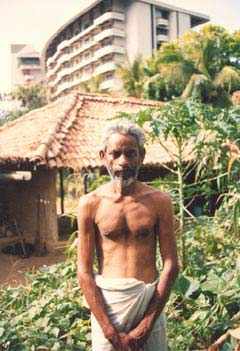

| The Samudra Cottage, circa 1994 |

British environmentalist Dr. David Bellamy provided the $15,000 it cost to build the Samudra Cottage (far more then the same structure would have cost to construct in a rural setting where all the materials and skilled workers are close at hand). The 1989 Festival of Lanka was a resounding success and publicity coup for the Taj Samudra and Cultural Survival. But after the festival the question arose: what to do with the Samudra Cottage now that it was there? The management decided that it should remain as an ongoing exhibit of rural Sri Lanka. Cultural Survival would occupy and manage the cottage.

Farmer-folklorist Mudiyanse Tennekoon supervised the project and lived there whenever he was in Colombo. Much to everyone's surprise, the Samudra Cottage survived and thrived for nearly seven years before it succumbed to the commercial ambitions of the Taj Samudra management. The Samudra Cottage was by no means a squalid miserable mud hut in the sense that most people might expect. Rather, it was a faithful model of a village headman's residence designed by leading architect Ashley de Vos who was an authority on traditional village architecture. Complete with two bedrooms, a kitchen and extensive verandahs, the Samudra Cottage had a spacious ambience and feeling of closeness to the earth -- even the seats moulded to the walls were earthen as well as the raised sleeping platforms in the bedrooms which doubled as storage rooms.

Within a few years, the Samudra Cottage with its cow-dung floors and walls, lush surrounding garden and authentic rural residents had fulfilled its promise as a model exhibit of country life in the heart of the city.

| During the 1993 International Year for the World's Indigenous Peoples, Dambana Wanniyal-aeto tribal elders stayed 'naturally at the Taj" at the Samudra Cottage Right: Sudu Bandiya |  |

Government officials, religious dignitaries of every religion and media personnel who visited the Cottage were invariably astonished that a piece of the fertile tranquility of rural Sri Lanka could be found in the shadow of a towering 5-star hotel in the middle of Colombo. Lecture-tours for Sri Lankan and foreign school groups were regularly conducted by Farmer Tennekoon, ecologist Dr. Ranil Senanayake and/or myself. Banana, papaya and aracenut palms grew in profusion; so dense was the foliage around the Samudra Cottage compound that few people including even hotel staff could locate it without a guide to show them. Under Farmer Tennekoon's direction, the Cottage became nearly self-sufficient in organic produce. Tropical songbirds found the lush surrounding a congenial refuge in the city, an island of sorts in the midst of the concrete desert in every direction outside the walls of the Taj Samudra.

Visitors fortunate enough to find their way to the Cottage compound had to cross a threshold separating the ordered environment of the traditional homestead from the surrounding spirit-infested jungle. Strategically-placed totems warded off the spirits of chaos and disorder that populate the island even today. Suddenly the visitors found themselves transported from the concrete and glass environment of the hotel into another realm or another time.

One had to walk upon narrow bunds placed between garden plots, halting often to study the species of garden plants. Passing the wewa or earthen water tank, one came to the kamata or threshing floor which doubled, here as anywhere in Sri Lanka, as the stage for dramatic fertility rituals including masked dances and ex tempore songs sung in ingiya, the twilight language of the kamata where spirits of different realms mingle.

| Farmer Tennekoon shows Theo a variety of betel leaf called Naga Valli. Long ago when Naga (serpentine) spirits visited this world they brought with them their favorite variety of betel leaf (chewed with lime paste and arecanut) as an offering to the humans who were living in Lanka at the time. The whole Samudra Cottage garden was planted with indigenous plants as seen in the photo. Theo came for three months in 1991 at age 15 on Cultural Survival's Discover Lanka educational program. |  |

If you were to enter the compound by day, you would feel that you were no longer in Colombo but somewhere in the Wanni region of Sri Lanka. Here songbirds warbled; the occasional mongoose kept the compound free of snakes. A lean, loincloth-dressed farmer, either Tennekoon or Appuhamy, would tend the garden a few hours in the morning and relax during the heat of the day, which in any case felt less stultifying here than elsewhere.

And from 1992 to 1994 you might find me there also, when I was not manning Cultural Survival's complimentary office provided rent-free courtesy of the Taj from 1989 to 1995. Admittedly, working by day in a 5-star hotel office and residing by night in a mud palace all within the same 14-acre grounds, is a real luxury in today's world, offering literally the best of both worlds without having to commute between the city center and the island's rural heartland, the Wanni. In two minutes one could escape the artificial air-conditioned environment of the hotel and pass out of the city altogether, as it were, into a greener, quieter and slower world. Here, barefoot and clad only in sarong, one could enjoy herbal teas from the garden, cooked delicacies made of fresh stone-ground rice flour or organic whole grain rice cooked in earthen pots over a wood fire with delicate curries made from our garden's own produce. No one who came once to our 5-star mud palace ever forgot the experience.

This, of course, was on ordinary days. When there was a special occasion, such as a reception or dinner party or artistic performance by night, the magic was such that even we who lived there year-round felt swept away as well. Like most rural homes in the Wanni, the Samudra Cottage had no electricity. So to illuminate the narrow path to the cottage, torches soaked in coconut oil were set ablaze and earthen oil lamps placed in niches on the verandahs. The effect was nothing less than magical, particularly when combined with live tabla and sitar music and spirited conversation among guests from all corners of the island and, indeed, all corners of the world.

Perhaps the rave reviews of visitors and the stories that circulated about the Samudra Cottage were what finally sealed its fate. The Taj Samudra hotel was not making any money from the Samudra Cottage phenomenon (nor were we who maintained it). The message of trusting and respecting the wisdom of the villager and of emulating their simple lifestyle did not sit well with the management of a hotel that catered to the diametrically opposite mind-set of wealthy travellers and businessmen. Finally the management announced that the hotel wanted to 'develop' the land that the Cottage was situated upon. After all, we had occupied the land for six years and there was concern that if we squatted there for seven years, we might claim squatter's rights. But we left peacefully and even willingly.

And the Taj Samudra to this day has not found a better purpose for the compound than to allow it to remain as a haunted ruin, a monument to the message that it so generously subscribed to, once upon a time.

Visit the Samudra Cottage photo album

For information about efforts to preserve the traditional culture of Sri Lanka, visit these pages:

Kataragama Devotees Trust

E-mail: kataragama@gmail.com

Living Heritage Trust ©2021 All Rights Reserved

For information about efforts to preserve the traditional culture of Sri Lanka, visit these pages:

|

Kataragama Devotees Trust |

| Living Heritage Trust ©2021 All Rights Reserved |

In 1989, Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka was formed with the object of representing the views and interests of traditional villagers who still form the majority of the island's population. The idea was to show that traditional organic lifestyles should be not merely tolerated but studied and emulated if Sri Lanka is to break the cycle of social unrest and environmental degradation brought on largely by the introduction and resulting hegemony of modern Western values and patterns of comsumption.

In 1989, Cultural Survival of Sri Lanka was formed with the object of representing the views and interests of traditional villagers who still form the majority of the island's population. The idea was to show that traditional organic lifestyles should be not merely tolerated but studied and emulated if Sri Lanka is to break the cycle of social unrest and environmental degradation brought on largely by the introduction and resulting hegemony of modern Western values and patterns of comsumption.