|

|||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

Kataragama - The Ceylon Shrine of God Kadira

by M.D. Raghavan, Ethnologist Emeritus, National Museums of Ceylon

|

|

|

Kataragama devales as they appeared in 1950

|

Traditions

Among the most popular of the gods is Katragama, a name unique in itself, standing for the name of the god, as for his shrine also signifying the village of Kataragama, in South East Ceylon, where on the left bank of the Menik Ganga, nestles in its enchanting jungle setting the mystic shrine to God Kadira. A shrine of great antiquity, foremost in all Ceylon as a popular pilgrim resort, tradition has it that King Dutugemunu in the second century BC built the present shrine in fulfillment of a vow commemorating his successful expedition against King Elara (205—161 BC). Round this episode has grown the Sinhala folk poem “Kanda Māla“ (Garland for Skanda), opening with a narration of the coming of the god to Lanka.

God Siva once told his Sons Kanda Kumaru (Skanda Kumara) and Ganidu (Ganesa), that he would give a mango to whoever would first encircle the three worlds. Skanda started off on his golden peacock to carry out the adventure to the very letter. Ganesa cleverly encircled Isvara, saying that the God in himself constituted the three worlds. Siva was so pleased that he gave the mango to Ganesa. Skanda returning was so enraged that he delivered a well-aimed blow at Ganesh, who rolled down breaking one of his tusks. Siva banished Skanda who, coming to the world of mortals, took his abode at Kataragama of South Ceylon.

Amusing as an imaginative story in the playful encounters of the two brothers, the puranic background of the god is as narrated in Skanda Purana: that God Skanda came into being in the course of the devastating war between the Devas and Asuras. Smarting under the blows inflicted on them by the Asuras, the Devas in a body waited upon God Siva, so as to devise a means of crushing the Asuras. The answer was the creation of God Karttikeya. Endowed with the lance, the gift of his mother Parvati, Skanda encountered the Asuras and annihilated the Asura forces.

The god’s romance for Valli, the maiden of the wilds, daughter of a Vedda chieftain, is among the legends that associate the god with Lanka. Pursuing the daughter of the jungles, Karttikeya arrives at the jungle resort of South Ceylon now known as Kataragama the abode of God Kadira, where the God marries her. The visitor to Kataragama today, if he scales the walls outside the pillared hall, will notice a series of panels in mild colours, illustrating the life story of Valli from infancy to maidenhood, ending with her marriage to the God. One of the scenes shows the abundant hill crops of maize, with birds hovering over and settling over the maize cobs, Valli sling in band scaring away the birds, a pictorial version of the episode in the career of the God.

To resume the incidents sung in the Sinhala folk chronicle “Kanda Maala”: Prince Dutugemunu preparing for a final assault against the Tamil King Elara was warned in a dream not to embark on the expedition, unless he secured the divine aid of the God of Kataragama. Appearing in dream to his devotees is among the notable features of the cult of this particular divinity. No time was lost to do the trek to Kataragama “where the river flowed with water, though no rain fell”, in the words of Kanda Maala, Miracles are yet another feature of the supernatural here and many are the miracles which are part of the chronicles of Kataragama.

The Prince reaching Kataragama went through severe penances for divine blessing. Lost in meditation, the Prince fainted. Recovering consciousness, the great God stood before him and conferred on the royal suppliant the boon sought. The Prince recovered sufficiently to make a vow that on his return from victory, he would rebuild and endow the temple. Confident of victory, Dutugemunu entered the field. The final stages of the fight were signaled by single combat between the two adversaries. Elara was vanquished and killed by an arrow from Dutugemunu, who recovered the throne.

The garland of verses, the Sinhalese folk poem “Kanda Maala”, in true poetic flight speaks of a building of three storeys which the King erected with an entrance gateway of seven steps, as thanks offering to the god of war. On the south, he erected the shrine to Ganesh, a kitchen for making offerings, an altar for flowers, and a kovil for goddess Pattini. Four furlongs off, he built the Kiri Vihare and formed parks (udyana) around the seven sacred hills.

If the structure of the Maha Devala as Dutugemunu built it was of the imposing proportions described in the folk poem, nothing of it is evident today. The shrine room is of moderate proportions, with the outer wall bearing a series of moldings. In front is a pillared hall where the devotees assemble and make offerings. Within the quadrangle is the temple of Ganesh. Outside to the right is the kovil to Teyvayani (Devayani) Amman. A few yards away [editor's note: 300 yards] from the Maha Devala, is the kovil to Valli Amma.

A Pilgrim's Day

Unpretentious as the structure is, the god is the most omnipotent, and no god in Ceylon is more assiduously propitiated than the god of Kataragama. Whether in personal or national causes, prayer is laid at the feet of the god.

Esala (roughly July—August) is the month sacred to the annual festivals of the Ceylon devalas, the first of such gorgeous events being the Kandy Esala Perahera, the celebration in honour of the sacred Tooth Relic at the Temple of the Tooth (the Dalada Maligawa), jointly with the festivals of the Natha, Maha Vishnu, Kataragama and Pattini devalas of Kandy. During the season of the annual celebrations at Kataragama, the narrow road from Tissamaharama, the nearest halting station to the shrine, a twelve mile tract, is closed to all vehicles and the path left unrestrained to the thronging mass of pilgrims.

Footsore and tired, the pilgrim reaches the gently flowing Menik Ganga. Reaching his destination, a sense of calm and tranquility overpowers him. Bubbling over the sandy bed, the stream here is knee deep. Wading over to the opposite bank, the pilgrims prepare for a full bath. Quite a few cross the river over the suspension bridge, creaking and groaning with age. Refreshed by the dip in the cool waters of the stream, no time is lost to collect the essential offerings of coconuts, plantains, camphor and joss sticks, neatly disposed in brass rattan or basketwork trays, and the pilgrims wend their way to the shrine to be in time for the morning puja.

The resonant sounds of bells ringing and conch blowing proclaim the puja in progress. Crossing over the arched gateway, pilgrims enter the hall of offerings. The sight here is ecstatic. To the peeling of bells and blowing of the conch, men and women of all classes, high and low, rich and poor, freely move about between huge brass lamps, in an air thick with the perfumed smoke, lighting joss sticks and camphor, or offering players, down on their knees or standing with bowed heads and hands in prayer. The learned in the sacred lore, chant long verses in Sinhalese or Tamil in adoration of the one God revered alike for spiritual salvation as for his virtues of delivering the goods of this world; the God who is looked to in all the ills that man is heir to. The officiating priest (kapurala) presently emerges from the sanctum sanctorum, holding a brass plate of the holy ash, and sandal paste. This is the occasion for the worshipers to drop their offerings in the plate ranging from a few cents to rich gifts in money or jewelry (such as silver, gold or tungsten rings).

Theertham (sacred water) and sandal paste are offered to all, and every one has a helping of the holy ash. Charmed coconut oil is another little thing that women do not omit to collect. Their faith is great in the efficacy of the “Kataragama oil“, a family remedy for such ailments as the head-ache.

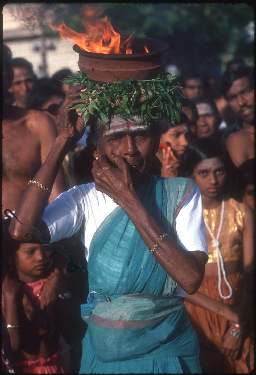

While this in short is a normal day at Kataragama, the scenes and sights during the days of the annual celebration are too exuberant and exultant for words. Mysticism and the supernatural, reach their climax during these days. Round and round the devala go pilgrims with mouth gagged, silver arrow-headed pins piercing lips or cheeks end to end, or tongue pierced. With hooks pierced in his back, a pilgrim hangs from a beam or drags a decorated cart. Others measure their length on the burning sands, falling, rising and walking alternately. Mortification of the flesh and infliction of physical pain for atonement of and reparation from sins, and acquiring of spiritual salvation, are characteristic of the abundance of religious zeal at festival time at Kataragama.

Sacred and special to the God is the kavadi, the arched shoulder pole gaily decorated with lustrous tinsel and coloured paper, adorned with bunches of the peacock feathers, which the devout pilgrim sports about on his shoulders, stepping and dancing to the tune of the drumming. The pilgrim carrying it is invariably one who has taken a vow to do the pilgrimage on foot all the way. Mysticism underlies the wearing of the arrow headed silver skewer by the devout votary. The faith is that the particular devotee is the chosen of the God for this investiture. The God appears in a dream enjoining on him to wear the insignia of the God, the mudra. The belief is also held that the same night the goldsmith of the village has a dream that he is to make the spike for the man who will duly appear. The actual investing of the kavadi pilgrim, with the sacred insignia, has its own ceremonial ritual.

|

|

The Kavadi in a portable form symbolises the elaborate Kavadi car (the thêr), the annual progress of which through Colombo roads from the Sea Street Hindu temple to the Hindu temple at Bambalapitiya, and back to the Sea Street, is an annual event of sacred and spectacular interest. The Vel -- the ayudha or weapon of the God -- the long lance, has given the name to this the Vel Festival celebrated at this season in Ceylon in the shrines sacred to the God.

The Fire-Walking

The concluding stages of the festival, are marked by the fire walking ceremony. Hue walking emblazons t lie annual festivals at a number of other shrines too in Ceylon, notably the Draupadi Amman Kovil at Pandrippu in the Eastern Province, and Udappu near Chilaw, a kovil of Hindu Karawas dedicated to the Pandava princes and Draupadi, the annual celebration of which terminates with the fire walking ceremony. Fire walking is the expurgatory ceremonial at all these shrines, refining, chastening, and purifying everything evil by the performance of the ritual passage over fire. The ceremony at Kataragama is among the most elaborate and spectacular of all, walking over an incandescent mass of embers raised by burning logs about fifteen feet long and four feet high. The leader, the Gini Pagana Sāmi, and the group of fire walkers proceed to Menik Ganga at dawn. After a bath in the stream, a procession starts for the temple, reaching which led by the leader, all walk over the red hot cinders, with faith in the God as their only physical protection.

The Water-Cutting

Yet another ceremony follows, which rounds off the festival, the Diya Kaepima or the water-cutting ceremony. Observed in the early hours of the morning, the Diya Kaepima is the consummation of the annual festivals at all the devales of Ceylon. Headed by the Kapurala, a procession starts for the Menik Ganga. Reaching the river the Kapurala wades in the water and flashes the golden sword. As the waters heave he empties the kendi of water in his hand, plunges the vessel in, and fills it with water. The procession starts back to the devala, where the vessel of water is deposited in the shrine room. Here it remains until taken out at the next annual festival.

In Ceylon, Kings and the State have ever been deeply conscious of the place of water in the life of the island. As a ceremony in sympathetic magic, Diya Kaepima is meaningful, seeking divine intercession for copious rains and adequate supplies of water to man and beast alike. Filling of water vessels and the pouring of water, are symbolic of the rain-making magical ceremonies. Instituted by the Sinhalese kings as an occasional ceremonial in seasons of famine or extreme drought, rain-making rituals became ingrained in time as the dominant idea in holding annual festivals at the devales, propitiating the gods for the prosperity of the country.

Legends

Among the legends of Kataragama is the one relating to the sacred chair or throne of Kataragama Deviyo, a description of which, often quoted, runs thus:

“A sort of easy chair, covered with the skins of cheetahs, on which the bows and arrows of the different gods and goddesses are placed and having a fire by its side which is never allowed to be extinguished. The chair is said to be formed of a sort of sacred clay from the banks of the river Ganges, and is held in great veneration as having been the seat of the founder of the Devala, who is represented to have stepped from it form earth to heaven without passing through the sates of death."

The God meets evil in his own sententious manner. Ribeiro, the Portuguese historian, relates an interesting story of how about 150 Portuguese and 2,000 Lascorins (South Indian Christians) under the command of Gaspar Figueira de Cerpe, becoming quite excited with the wealth stored in a pagoda held in great reverence rushed into the forest to rifle the pagoda, with its vast wealth of gold, jewels and precious stones enshrined from time immemorial. Says the Portuguese historian Ribeiro:

When we came near to the spot where they said the pagoda stood, we took a native residing close to the spot and our Commander inquired from him if he knew where the pagoda was. He replied that he did, and that it was close by. He acted as our guide and led us through a hill covered with forest which was the only one in the district, and this we wandered round and recrossed many times. It was certain that the pagoda was at the top of it. But do not know what magic it possessed, for out of the four guides whom we took, the first three were put to death because we thought that they were deceiving us, for they acted as if they were mad, and spoke all kinds of nonsense, each one in his turn, without the knowing of the others. The last two deceived us and did exactly the same, and we were forced to turn, without the knowing of the others. The last two deceived us and did exactly the same, and we were forced to turn back the way we had come without effecting anything, and without even seeing the pagoda which is called Catergao.”

Viewed against the background of early history and the geographical setting, the study of Kataragama becomes more objective and intelligible. More than any other factor, its situation in the heart of South East Ceylon determined the part it was to play in the life of the land South Ceylon the Ruhunu of early ages was not the neglected and the comparatively little known corner of Ceylon that it degenerated to following the decline of the Sinhalese monarchy. It was a region very conspicuous in the Middle Ages, next in importance only to Raja Rata, within which was included the capitals of the Kings. That Kataragama in the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC was the seat of a Kshatriya clan whose representatives “the nobles of Kajaragama” were present at the festival held at Anuradhapura on the arrival of the great Bodhi tree, we are told in the Mahavamsa. Ruled by the sons of the Kings, and a refuge of the Kings themselves in times of political reverses, Ruhunu was next to Raja Rata, the best governed part of Ceylon. As the Ruhunu Maha Devala, the war god of Kataragama was the supernatural force to whom kings and princes supplicated and prayed in a difficult situation such as confronted Dutugemunu, the prince of Ruhunu at the time, faced with the task of emancipating the Island as already narrated.

In performance of his vow, the Prince endowed, enriched and extended the temple. How far back in point of time the temple dates, we are left to surmise. Tamil traditions, reflections of which are caught in the Kalpana Vaipaya Malai, ascribes to Vijaya the building of a temple to ‘Kadirai Andavar’, a tradition which disposes us to trace the worship of the God at least to the days of Vijaya (5th Century BC). With the goal of political stability set before him it is conceivable that Vijaya was not unmindful of divine aid in his task of overcoming all impediments towards achieving full sovereignty. That Vijaya either inaugurated or advanced the worship of an already existing shrine, as his illustrious successor Dutugemunu did later, is a reasonable conclusion. His sway over South Ceylon, the God of Kataragama commands the allegiance of all Ceylon, with the numerous shrines dedicated to the God distributed all over the Island.

The cult of the God has declined in North India since the early Middle Ages, when it was vigorously functioning. A reflection of this may be found in Kalidasa's great classic “Kumāra Sambhava” or the God's Birth. The great centres of Skanda worship today are situated in Ceylon and South India, where several shrines are dedicated to the God known under a plurality of names Kārttikeya, Kārtikesa, Kadira, Katiramen, Kadirgamar, Skanda, Kandaswāmi, Muruga, Arumugam, Shanmuga, Subramaniya, and Bāla Subramaniya.

The Author

M. D. Raghavan was President of the All-India Oriental Conference, XIth Session, Section of Ethnology and Folkore, and was the first Head of the Department of Anthropology, University of Madras.

As ethnologist in the Department of National Museums of Ceylon, from 1946 he conducted the Ethnological Survey of Ceylon. The results of his studies in the Survey are published in the form of monographs in the Spolia Zeylanica, the Journal of the National Museums of Ceylon. Supplementary to these appeared a long series of research studies in Ceylon Today, the Journal of the Department of Information, Government of Ceylon; New Lanka and other journals, besides several popular articles in the Ceylon and Indian press.

| Living Heritage Trust ©2019 All Rights Reserved |