|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Kataragama: Beyond the Festival, a Story of People and Faith

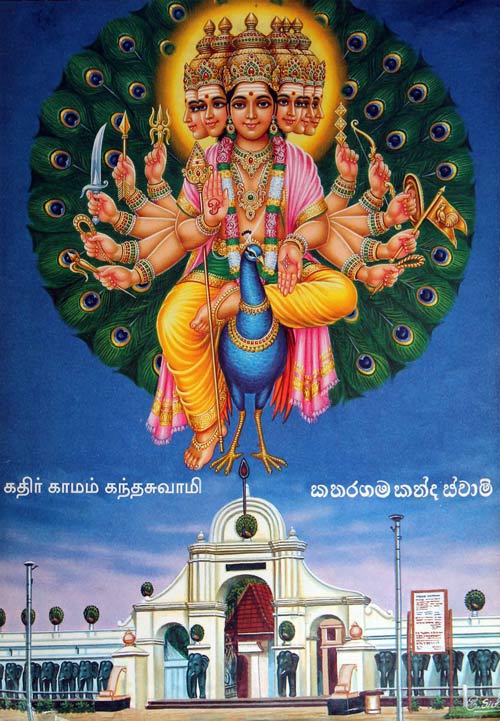

By Duvindi Illankoon and Shaveen JeewandaraSynonymous with rituals and godly belief, Kataragama in southeast Sri Lanka is a place of worship that every Sri Lankan pledges to visit at least once in their lifetime. Inside the temple--amidst the heady scents of incense and camphor--thousands of devotees reach up to ring the bells hanging overhead and evoke the blessings of Lord Kataragama. ‘Muhunu sayaki – ath dolasaki – Mayura pita vāhane’ says the popular Sinhala verse, describing the Kataragama Deviyo, or Lord Kataragama, as having six faces and twelve hands, mounted atop his vehicle – the peacock. The Kataragama Esala festival draws in large crowds of people -some who make unfailing visits every year- turning the sacred land into a kaleidoscope of colours, rhythm and devotion. But our journey revealed that there is more to Kataragama than merely worship – here you’ll also find a charming tale of coexistence and inter-communal unity entrapped in its hallowed soil, especially during the festive season. The present day journey to Kataragama is significantly less arduous owing to the development of infrastructure, and the scenery one passes has morphed over the years from a drab townscape to one of bustling enterprise. However the Ruhunu Kataragama Maha Devalaya or the main devalaya has stood from time immemorial, with little or no visible change to its simple architecture. Even its thatched roof is identically replaced every year mid-festival. In the quest for an all-defining victory in the battle against King Elara and the Chola troops, King Dutugemunu was believed to have had an encounter with Lord Kataragama (Skanda Murugan). Upon this encounter, King Dutugemunu asked for the strength to overpower his enemies. With his boon being granted, the Kataragama Devalaya was subsequently built in fulfilment of the vow. Legend says that the King had asked what should be done as a means of fulfilling the vow and Lord Kataragama replied by striking an arrow in the direction of Wedahitikanda from Kiri Vehera, and requested a temple be made at the point where the arrow had struck. Today, thousands flock to Kataragama to worship Skanda Murugan but it is also one of the solosmasthana – sixteen sacred sites in the island said to have been visited by the Buddha.

“King Dutugemunu made a vow that as long as the sun and moon remains, the people of the land he united after victory shall pay their respects to the Kataragama Deviyo,” says Somipala Ratnayaka, the chief Kapu Mahattaya (shaman-priest in charge of the temple) of the Ruhunu Maha Kataragama Devalaya. Now aged 75, Mr. Rathnayaka was inducted to his duties at 16 and officially undertook his position as chief Kapu Mahattaya back in 1975, after the demise of his father. “The festival is one that is held with great devotion and happens with the same level of enthusiasm every year,” he tells us. We’re told that only on four instances has it ceased to happen throughout recorded history: in 1910 and 1911 owing to the spread of cholera and in 1971 and 1989 owing to the troubled situation of the country.

We come to learn that the duties of the festival are carried out by the descendants of the initial 555 loyal servants that King Dutugemunu appointed to look after the devalaya. This includes the Deva Kapugollo, panikkiyas (drummers), natuwwas (dancers), the Adhikaram, the Basnayake Nilame and the Kapu Mahattya who is heir to the role. An interesting fact is that although all the auspicious times are decided by the kapu mahattayas, the beginning of the festival is symbolically marked by the hoisting of flags at the Kataragama Mosque and Shrine – a simple yet powerful shrine -housing the tombs of two Islamic saints- intimately associated in quranic lore with Hazarat Khizr (alai), ‘The Green Man’. In a symbolic gesture of ineffable unity, the chief incumbent of the Kirivehera Raja Maha Viharaya, the chief incumbent of the Kataragama Abhinarama Viharaya along with the Basnayake Nilame and chief Kapu mahattaya visit the mosque during this ceremony which marks the beginning of the festive period. “Such is the beauty of Kataragama,” says Mr. Rathnayaka, “It is a place where devotees across all four religions of the country claim with their own folklore and come to seek refuge in the Kataragama Deviyo as one, and this sacred ground is equally welcoming to all.” Kumanaa agamak wunath minussunta thiyana prashna ekai, or the problems people face are the same regardless of race and religion, he tells us. Mr. Rathnayaka believes that stating your sorrows to Lord Kataragama brings a sense of tranquillity to the mind, regardless of your belief in deities and the supernatural. The festival finds its beginnings in the kap situweema (planting of trees), which takes place as preparation for the festival and occurs 45 days before the festival. Mr. Rathnayaka explains that the officials known as gotu mahaana and pandam mohandhiram venture into the jungle and locate two stumps of kiri gas approximately nine hand-widths in length. “These are then inspected and cut out by the kapu mahattayas, cleaned, draped in white and paraded to the banks of the Menik ganga where it is bathed with the water and scented with dehi, incense and camphor.” Later they are taken to the Valli Amma devalaya and subsequently paraded to the Maha Devalaya at dawn the next day, where they are planted. The sixth day of the festival is regarded as one of the most eventful with multiple events of importance. Firstly, the display of the tusks of King Dutugemunu’s royal elephant, Kadol Etha in front of the Maha Devalaya. The two tusks are on display until the water cutting ceremony at the end of the festival. On the same day, saffron flags are hoisted at the Thevani Amman Kovil and an almsgiving ceremony is held under the auspices of the Basnayake Nilame. The udu wiyan bandeema or weaving of the thatched roof of the Maha Devalaya also happens on this day.

During the fifteen days of the Esala festival, the streets of Kataragama light up with parades, dances and ritualistic acts which includes fire-walking, piercing cheeks and tongues with needles, hanging from iron hooks, and kavadi (an arched pole decorated with peacock feathers) dancing, performed by devotees fulfilling their vows. The main perahera sees a grandly caparisoned elephant carrying the Kataragama Deviyo, flanked by dancers and drummers. It advances in a carefully choreographed procession from the Maha Devalaya to the Valli Amma Devalaya to signify the visits of Lord Kataragama to his sweetheart, the jungle princess Valli. The final perahera proceeds from the Maha Devalaya upto the Kiri Vehera, to the Valli Amma Devalaya and from there back to the Maha Devalaya. The festival ends with the Diyakapimey Amangallaya (water cutting ceremony), where a ceremonial sword is used to part the waters of the Menik Ganga, and pots of water are collected from the point of parting – its touch said to invoke good luck. The vehicle park outside the devala entrance is swarming with vendors of all trades. One can find everything from talkative flower vendors to seedy tattoo parlours. But what takes prime place is the assortment of fruit baskets that devotees place as offerings to Lord Kataragama. They come in different sizes- the more you pay, the more fruits you get which some devotees may have translated as ‘bigger the basket, bigger the merit’.” This temple is not one that asks for anything from the people other than their wholesome devotion,” says Mr. Ratnayake, “Whether you offer a fruit basket or not, the Kataragama Deviyo will bless you for your loyalty.”

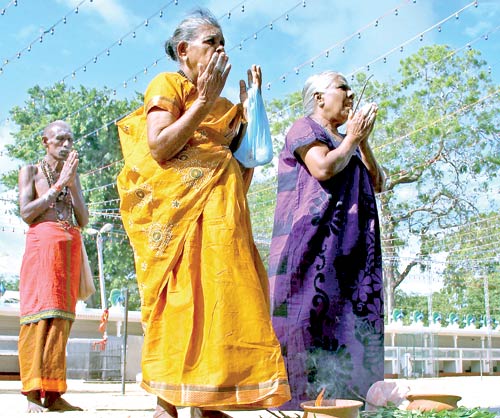

This faith in the Lord Kataragama has manifested itself in the minds of everyone here; be it the devotees, the temple’s officers and the vendors outside. We speak to S.M. Mohotti, who leads a group of devotees intending to walk over hot coals on the ninth day of the festival. A Kataragama tradition, this ritual is carried out based on nothing but unwavering faith. “I have been coming here for a long time,” he says. “Every year, I’m still amazed at what happens.” Nadeeka Baladurage, Sirimavathie Kodithuwakku and Nandani Menike are with Mr. Mohotti and say belief in Lord Kataragama is all they need to tread on the blazing fire. “None of us has endured a single blister or even pain,” says Mrs. Baladurage. For this ritual one must prepare well, however. The devotees abstain from meat products and alcohol and maintain good hygiene at all times. On the perimeter of the temple, we make a stop at a colourful shop selling the kawadi used by dancers at the Esala Perahera. J.H. Rohana has been doing this for forty years, making and selling both Murugan kavadi and bhakti kavadi to devotees. His father used to do the same business, with another partner (they were known as Silva and Sellai by the regulars). Rohana is wary of selling these to those who have not prepared adequately for the task. “I had a friend who didn’t prepare properly, and he passed away during the festival,” he says ominously. “After some time here you get used to things like this.” We also meet S. Tennekoon at the temple, here with his family and friends. Tennekoon is a regular at Kataragama, he has come here since he was young. “When we have problems we come to Kataragama to make a pledge and ask for blessings,” he says. Tennekoon is of the younger breed of devotees who visit the temple and says more people must come with a greater understanding of how Kataragama works. “We don’t eat meat or fish for days beforehand,” he points out. “You must prepare the right way if you want your blessings to be heard.”  Walk of faith: Pilgrims from the North approaching Trincomalee on the Pada Patra in 2005

Courtesy: The Sunday Times (Colombo) of July 6th 2014 Buddhist traditions of Kataragama

|

|

|