Kannan Arunasalam goes on a pilgrimage with an elderly aunt to a Sri Lankan Hindu shrine. It attracts people of all faiths, but it is increasingly overtaken with Buddhist trappings, revealing the political fissures in Sri Lanka.

My elderly aunt has for many months asked me to join her on a sort of pilgrimage to the little town of Kataragama - in the South East of Sri Lanka - to visit what's become a kind of interfaith shrine.

Mami, as I call her, is my father's elder sister and is an active woman of 84. She puts her good health down to her devotion. So I decided to make the eight hour journey with my aunt and visiting parents in tow.

I had another reason for wanting to go: Sri Lanka's situation today is arguably graver than it's ever been. Tens of thousands of civilians are still trapped in northern Sri Lanka in the ongoing conflict between government forces and the Tamil Tigers.

The Tigers have been accused of using civilians as human shields, while the government's push for a final confrontation is likely to add to the already growing death toll. With so much bloodshed and the likelihood of more, this pilgrimage means a lot to me and my family.

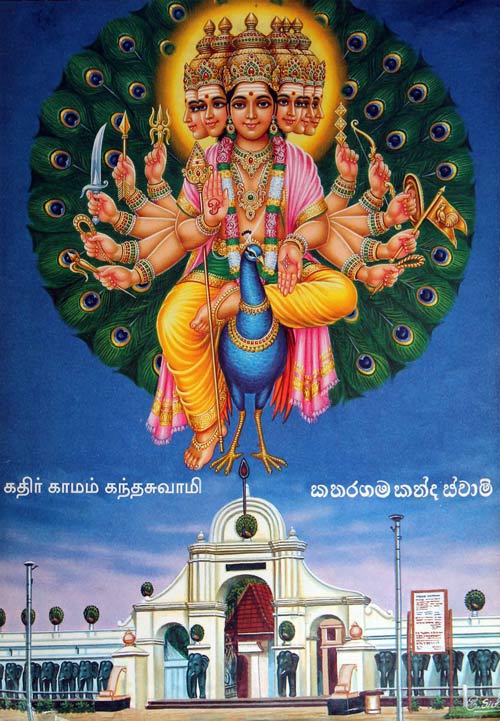

Here's why: Kataragama takes its name from Lord Kathirgaman, the six-headed Hindu God of War. The God of War carries a spear and travels on a peacock. Yet the town attracts large crowds from all the major religions of Sri Lanka, not just Hindus - who share a belief in the god's power to grant wishes. The most devoted walk on burning coals, drive tiny skewers through their cheeks and tongues or suspend themselves from hooks on their backs to huge juggernauts.

The Tamil Tigers venerate the God of War, and their propaganda pamphlets have verses about Lord Kathirgaman. The very same god is also the most celebrated deity of their Sinhalese enemies, who know the god as Kataragama Deviyo.

Reconciliation hope

Despite the conflicting allegiances, I've seen hope of reconciliation between communities in Sri Lanka through these multi-faith sites. In Colombo, I've seen a tiny Hindu shrine situated next to a Buddhist school. Every morning, two Buddhist sisters from the adjoining house conduct a ritual or pooja while a large Hindu crowd watches on with quiet respect. For me, they can be a model of peaceful coexistence.

But I've been disappointed to see other sites become overwhelmingly Buddhist, and crowd out other religions which also hold these places sacred. This encroachment - or what my father would call the "Buddha-izing" of Hindu sites - mirrors the wider conflict and its roots. In 2005, for example, the clandestine erection of a Buddha statue in multi-ethnic Trincomalee, in the east of the country, led to an outburst of ethnic tension.

So I wanted to visit Kataragama to see for myself whether the town had undergone a similar assimilation. My father fears it has. I'm hoping it hasn't.

As we traveled along the deserted seaside road, a punctured tire halted our journey. So Mami recited some protective mantras to ward off any further delays and dangers, and we arrived safely at the guesthouse in the late evening.

Religious fusion

We rose early the next morning to climb the town's sacred hill. And walked past small hillside shrines dedicated to other deities where my family stopped to pray and receive offerings of ash from the priests.

These priests or aiyars were Buddhist, now well versed in Hindu devotional texts. One aiyar even sang to us in Sinhala.

At the top of the hill, Buddhist prayer flags hung over the bronze vel (pictured above right), the symbolic weapon of Lord Kathirgaman, in a striking fusion of Buddhism and Hinduism.

We then made our way down to the main temple where we joined others for the pooja. Five women performed a swaying ritual with lighted oil lamps (pictured above left - mami is at the left of the photo).

Lord Kathirgaman's reach was evident when, across from us, I saw a Veddah - a descendant of the indigenous people of Sri Lanka - resting the ubiquitous axe over his shoulder (pictured below right)

At the end of the pooja, the head priest, bare-chested and dreadlocked, directed the crowd to ring the temple bells that hung over our heads. We all took turns pulling on the ropes and filled the air with a cacophony of chimes.

Minorities overshadowed

For my father, what we saw was only another example of how the majority ethnic group is slowly overshadowing minorities. But mami seemed oblivious to the politics symbolized in the trappings of Buddhism. Her God is here, in the stone and spirit of the temple.

When we have a quiet moment, she encourages me to say a prayer at this time of upheaval in Sri Lanka. I find this an odd concept: a prayer for peace to the God of War!

Mami admonishes me for my irreverence. Then I remember that seventy thousand have died in the conflict so far. Hundreds of thousands wounded. Over a million displaced from their homes. And right now, over one hundred thousand civilians have nowhere to turn. So I acquiesce, bow my head, and pray.

Courtesy: Radio Netherlands Worldwide

| Living Heritage Trust ©2021 All Rights Reserved |