|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From Kailāsa to Kataragama:

|

|

| Mount Kailāsa in western Tibet and Kataragama in the far south of Sri Lanka form a near-perfect analog to the axis mundi or susumna nadi of yogic lore. |

|

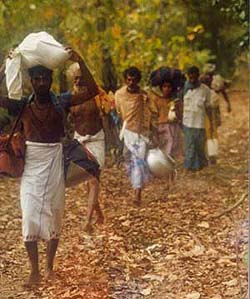

| Pilgrims both young and old from the North and East of Sri Lanka cross 100 kilometers of uninhabited jungle on foot to attend the Kataragama Esala festival. Photo © 1998 Patrick Harrigan |

|

| The Kataragama shrine (background) and its traditions originated among the ancestors of Sri Lanka's Wanniya-lætto or 'Veddas' (foreground). |

"Because he (German Swami Gauribala) is unable to remain summā,

he goes walking to Katirkāmam."

"Why do you search for the Lover who has taken His abode in your heart? He is the Light of Katirkāmam!" 1

In most world religions, pilgrimage is given relatively low status in the hierarchy of religious practices.2 But in one ancient yet still vibrant Śrī Lankan tradition, the practice of Pāda Yātrā or foot pilgrimage demonstrably embodies profound metaphysical truths while serving as a working framework or matrix for the exploration of progressively subtler levels of religious practice that have long escaped the attention of non-participant observers. Far from being a merely outward practice suitable only for laity or the exceptionally naive religious specialist, pilgrimage in the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition is a comprehensive exercise of body, mind and spirit having ramifications far exceeding the suppositions of 20th Century indological scholarship.

Despite its great antiquity, stature and symbolic importance in Sri Lanka's multi-ethnic society, the tradition of annual Kataragama Pāda Yātrā has never been the object of modern scholarly study. This is partly because it takes place in remote districts in the North and East -- precisely the districts most affected by the ongoing conflict between insurgents and Government security forces -- and partly because Pāda Yātrā survives as a rural village 'little tradition', beneath the purview of older scholarship. Studies of Kataragama to date have tended to underplay the religious dimension of Kataragama as the tradition's custodians themselves understand it, focusing instead upon emerging social trends and regarding the Kataragama festival less as a religious tradition than as a release-valve for social tensions in post-Independence Sri Lanka.3 This study, however, surveys Sri Lanka's longest and perhaps oldest pilgrimage tradition from the religious perspective as articulated by the tradition's practitioners themselves and assumes that a religious tradition is best understood within its own frame of reference.

Among the ancient living traditions that survive in island Sri Lanka's rich cultural environment, few are as well known or as poorly understood as that of the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā. Starting from the island's far north and ending up to two months and several hundred kilometers later at the Kataragama shrine in the island's remote southeastern jungle, the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition has played a major role in propagating and perpetuating traditions of Kataragama throughout Sri Lanka and South India. Predating the arrival of all four of Sri Lanka's major religions, it is essentially a tradition inherited from the island's indigenous forest-dwellers, theWanniya-læto or Veddas, as the Kataragama shrine's Sinhalese kapurala priest-custodians themselves readily concede.

Prior to 1950 when a motorable road was extended up to Kataragama from Tissamaharama, the only way pilgrims could reach Kataragama was on foot or by bullock cart. All that has changed since then and now Kataragama is cheaply and easily reachable by regular bus servce directly from Colombo and other districts including the Eastern Province where the Pāda Yātrā tradition continues to flourish in an air of revival. Easy access has entailed a drastic change in the makeup of the pilgrims who visit Kataragama for the festival season; while a few thousand still walk through Yala National Park to the east of Kataragama, now hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankan visitors come as pilgrims and even as casual tourists.

This has inevitably eroded the consensus among pilgrims which gave Kataragama its air of sanctity and mystery, replacing it with a carnival-like atmosphere. And while the more devout pilgrims may regret the process of progressive secularization that continues to affect Kataragama, they also tend to explain these changes as being the will of the Kataragama god who, after so many centuries, remains alive and well and mysterious as ever in his ways of relating to humanity.

Because of the sheer length of the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā, since ancient times those who walk the distance (much of it through uninhabited jungle even today) tend to be dedicated religious specialists. The great majority of Pāda Yātrā swāmis and bāwās remain anonymous, but among them have been more than a few great saints, sages and siddhas beginning, it is said, with Skanda-Murukan himself who is the first among Pāda Yātrā pilgrims according to the tradition. These have included, notably, the renowned fifteenth century Tamil psalmist Arunagirināthar, who composed at least one Tiruppukal hymn at Kirimalai (near Kankesanturai on the far northern coast of the Jaffna peninsula), another at Tirukkonamalai (modern Trincomalee, a major sacred site on the traditional Kataragama Pāda Yātrā route) and fourteen at Kathir-Kāmam, '(the place of) brilliance and passion', i.e. Kataragama.4 More recent well-known pilgrims include Palkuti Bawa and Yogaswami of Nallur. The following account of Nallur Yogaswami's pilgrimage to Kataragama remains typical even today:

Subsequently by about the middle of 1910, Swami left on a solitary sojourn by foot along the Island's coastal belt eastward, and met many ascetics on the way. He moved freely with certain Muslim Sufi saints, Buddhist monks, and Veddha chiefs. He communed with Murugan in Kathirkamam, the Holy of Holies skirted by the Manica Ganga . . . from 1910, he had taken solitary long distance pilgrimages to Tiruketheswaram, and on to Wattapalai and Koneswaram at Trincomalee, and skirting the east coast by the foot path, he had spent his recluse days at Sittankudi, Batticaloa and Tirukkovil. Many a time, he had related incidents when he trekked the Vedda tracts of Moneragala and Bibile to reach the abode of Murugan at Kathirkamam, skirted by the Manica Ganga and the seven hills of Kathiramalai.5

Almost no records survive written in the pilgrims' own words, although British government agents made exhaustive records of the colonial government's efforts to discourage or restrict a practice considered to be unhealthy and unproductive.6 The perspective of dedicated foot pilgrims, however, was and remains radically different from that of most scholars and government administrators.

This study is based on the researcher's participation in the Pāda Yātrā from Jaffna to Kataragama in 1972 and a further ten times since 1988. Especially invaluable has been detailed instruction from the renowned Swami Gauribāla Giri, a German

| In 1910 during his sadhana period, Yogaswami of Nallur walked Pāda Yātrā from Jaffna to Kataragama. |

|

| Pāda Yātrā pilgrims (above, in 1992) face a long walk south along Sri Lanka's eastern seaboard to the Kataragama God's redoubt in the remote southeastern jungle. From Mullaitivu on the island's northeast coast, foot pilgrims walk for 45 days mainly through sparsely populated areas. Traditional pilgrims walk barefoot dressed in simple garb, sleeping in the open and living from alms offered by villagers. Combatants on both sides of Sri Lanka's ethnic conflict pay due respect to the pan-Indian wargod Skanda-Murukan and his colorful parties of foot pilgrims. |

|

| German Swāmi Gauribāla Giri |

The present study may be regarded as a continuation of German Swami's 'Mu research' (as he termed it) applied to the theory and practice of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā, of which German Swami was widely acknowledged as an accomplished expert. His distinctly antiquarian approach, developed through decades of fieldwork and patient study of diverse literary and oral traditions, informs the content and methological approach of the present study. German Swami deplored the approach of Western-trained researchers who insist on imposing modern values and assumptions upon oriental traditions whose raison d'etre lies entirely outside the scope of their research. In his view, the sincere researcher should seek to reproduce the findings of oriental traditions by replicating their methods whenever possible rather than to apply alien methods and assumptions. The present study therefore is derived from this researcher's efforts to duplicate the findings of German Swami and other practitioners before him.

|

| Contemporary pilgrims prefer to walk in large parties for the sake of security, as above. Due to the ethnic conflict, the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition almost died out in the 1980's, but resumed in 1988 on a small scale. Since the mid-1990s again thousands of Tamil pilgrims walk Pāda Yātrā from Batticaloa and Ampara districts. Pilgrims proceed as a group through Ampara District in 2007. (photos by Patrick Harrigan) |

The researcher's methodological approach therefore is both critical and problematic, for while most pilgrims will gladly speak about their experience of Pāda Yātrā, only a very few pilgrims among hundreds are qualified to speak authoritatively about the essential inner pilgrimage. And since the interior pilgrims who have penetrated deeply will not or cannot express their experiences except by allusion and metaphor, the earnest researcher has to build a picture of the essential mystical practice based partly upon the example or testimony of others but based to a greater extent upon firsthand experience.

Sacred Geography and the cult of Skanda-Murukan

The Kataragama Pāda Yātrā was Swami Gauribala's practical introduction to cosmography or sacred geography as he called it, the systematic study of what Eliade termed hierophanies, those rare, divine spots at which divinity reveals itself on earth.8 Island Lanka preserves a wealth of folklore said to originate from remote prehistory and puranic sources, including notably the Ramāyana, which still survives in the form of local place legends. Swami Gauribala's approach involved analyzing the relationship between sacred places and their associated legends. Having re-searched and dis-covered the principles of traditional oriental cosmography, he concluded that they should remain sacred and secret, i.e. evident but unarticulated. His contention was that anyone qualified to study a sacred science who studies that science in depth would arrive at the same principles and, hence, similar conclusions. Decades later, his contention appears at least partly confirmed.

The cult of Murukan (Tamil: 'tender or fragrant one') or Skanda (Sanskrit: 'leaper or attacker' from skand 'to leap or spurt'), like the god himself, has a complex, composite history. Western-trained scholars are quick to point out the composite nature of the god as an amalgam of two distinct yet structurally analogous deities, Dravidian and Sanskritic respectively. But among indigenous religious specialists and millions of devotees at large, there is no question that the diverse body of lore in Tamil, Sanskrit, Sinhala and other languages describes a single vigorous and complex deity familiar to both northern and southern traditions since antiquity.

Qualitative Space and Chronological Time

Whereas Semitic and other nomadic peoples tend to think historically in terms of time and genealogy, people of long sedentary heritage and markedly cultic outlook think in terms of space, typically postulating a 'center of the world' in their own midst.9 In South Asia, the geographical environment has played a major role in shaping Indian thought. India thinks in terms of qualitative or mythical space in which each place has not only its own outward characteristics but also its own significance for those beings who inhabit that space. Hence, in the traditional worldview of India, spatial differences are also qualitative differences. In qualitative space, not all places are equal and the directions of space also have non-spatial qualities, in contrast to purely mathematical Euclidean space in which all points and all directions are content-less, quality-less and equal. Of course, South Asia is no stranger to the concept of sacred time, either, since most of the calendar is sacralized; even the modern Gregorian calendar remains sacralized to a certain extent. Yet nowhere else in the world has the tradition of pilgrimage and sacred geography remained as pervasive and vibrant as in the Indian subcontinent.

Aaru Patai Veetu: The Six 'War Camps' of Skanda-Murukan

In the context of Tamil Nadu, sacred geography is invariably associated with the Aaru Patai Veetukal, Murukan 's six 'camps' or sacred sites associated with particular episodes in His divine career that are scattered across the length and breadth of Tamil Nadu, effectively homologizing the landscape of Tamil Nadu with the career of Murukan . In fact, there are only five patai veetukal; the number six should be understood not as a statistical tally but rather a significant number in numerology and sacred geometry, a sister science of sacred geography.

|

| |

In this aspect as Shanmukha 'the Six-Faced,' Skanda-Murukan is the Lord of Space, the Unmoved Mover abiding as a conscious presence at the source and center of the matrix of infinite possibilities -- our own three-dimensional world of embodied existence. It is precisely this aspect of Skanda-Murukan that is celebrated at Kataragama, where no icon is worshipped but only a small casket containing (or said to contain, for it is never displayed) the shadkona yantra or six-pointed magical diagram etched upon a metal plate. Indeed, in contradistinction to the tradition of Tamil Nadu, in Sri Lanka the entire career of Skanda-Murukan is said to take place at Kataragama, such that the God's six stations or directions of space collapse, or rather return, back into their source -- undifferentiated singularity.

|

| Southern Kailāsa: Seven Hills of Kataragama with Vedahitikanda (Katiramalai) at center. |

At Kataragama this principle also finds embodiment in the ezhumalai or Seven Hills, where the highest (417 m.) and 'best' peak, Katira Malai ('Mountain of Light') or Vedahitikanda ('The Peak Where He Was'), is homologized to the number seven signifying reversal, return, integration and completion or perfection in childlike innocence and simplicity (Tamil: cummā iruttal), which is the specific objective of kaumāra sadhana or praxis for aspirants in the tradition of Skanda-Murukan. This holographic quality of Kataragama, where the whole may be seen within any given part, permeates Kataragama not only on the levels of myth and ritual but even on the physical level of geography. Mention may be made here that in ancient times when sacred geography played an important role in the identification of powerful sites, a configuration of seven hills was considered to be the ideal location for the capital of a kingdom. Notable examples include Athens, Rome, Constantinople and Jerusalem as well as Kataragama, the capital of a virtual kingdom.

From Kailāsa to Kataragama: The mythical career of Skanda-Murukan

|

|

Lord Kataragama Skanda

|

Anticipating the momentous career that awaits Karttikeya in the southern continent of Jambudveepa (South Asia), the devārsi or divine sage (and troublemaker) Narada instigates a contest between Kārttikeya and his rotund elder brother the

|

| Skanda-Murukan quits his home on Mount Kailāsa, descends to India and heads due south to Kataragama. |

From the conventional standpoint, this union of high god and low-born earthly maiden is a gross mis-match. And yet, representing as it does the 'illicit union' of Spirit with the earth-bound soul, the legend of Kataragama has long served as a creative framework for the most diverse forms of mysticism imaginable -- the very hallmark of Kataragama down the ages and the wellspring of its well-deserved reputation for mystery and sanctity.

| The Labyrinth is a familiar motif in traditional Sri Lankan artistry.

Above: an example of a traditional woven floor mat design preserved among women of rural Kurunegala district expressing the motif of passage to the sacred center. Two sacred animals -- deer and elephant -- guard the entrance. Below: Kataragama Pāda Yātrā pilgrims experience the labyrinthine character of Deviyange Kæle, 'the God's own Jungle', an enchanted forest where unusual occurences may -- and often do -- occur. Pāda Yātrā pilgrims preserve legends and practices associated with particular sites en route. |

|

Pāda Yātrā as Passage into the Labyrinth

In traditions the world over, pilgrimage essentially refers to the passage or transformation of the soul that turns away from the periphary of the outward world of multiplicity and turns inward through progressively deeper levels of awareness to arrive at the sacred center. The sacred center is entirely within the contingent being's inherent range of 'infinite possibilities,' and as such it may also manifest outwardly at certain times and certain places in the socially-conditioned world of sense perception. When the essential sacred center within is seen to have its counterpart in a sacred geographical site, the 'two' passages may be combined or integrated or, rather, comprehended to be inward and outward reflections of one and the same sacred passage: the return from multiplicity to one's original nature at the center of the world. In Kaumāra sādhanā, this passage is also understood as the return to one's original childlike nature of wonder and innocence, in Tamil called cummā iruttal, a multivalent expression meaning 'being still,' 'remaining simple,' or 'just being.'

In Kaumara tradition, the Spirit's active yet covert involvement is the vital or magical ingredient that transforms Pāda Yātrā from a mere walking journey into the experience of spiritual passage through a maze of subtle dimensions that escape the attention of non-participant observers. By the power of an underlying presence that none can claim to understand, earnest pilgrims traverse through the shadowy world of outward appearances and penetrate deep into an effulgent interior realm of Kathir-Kāmam or 'light and delight.' For them the spiritual journey is not an empty metaphor but intensely vivid and real. In this sense, only experienced pilgrims can appreciate what it means to cross invisible thresholds and plunge into strange realms of sacred time and sacred space. Hence, the motif of the labyrinth or passage to the innermost sanctum finds application in spiritual traditions worldwide, particularly in the context of pilgrimage in the dual sense of outward journey and inward passage to one's metaphysical source or center.

Through a process of release from conventional notions of self, time, space and causation by 'coursing against the stream' of worldly opinion and habitual ideation, veterans of the tradition consciously aim to recover the amrta or ma'ul hayat, the Water of Life that others are said to have found before them. In order to arrive at its source, they may enter dimensions where what was once thought impossible can come to pass in the twinkling of an eye. Despite hunger, thirst, fatigue, illness and a host of very real dangers one may encounter when traversing jungle and areas of civil conflict, most foot pilgrims reach their destination in the outward sense at least. But the longer and deeper passage to the sacred center within is beset with trials and obstacles of even greater diversity and subtlety (often depicted as walls of fire or water) which effectively screen out all but the most dedicated and resourceful pilgrims.

From Kailāsa to Kataragama: Mystical passage via the axis mundi

Like his 'father' Rudra or Siva, Skanda-Murukan is a god associated with mountains and hilltops; his Wanniyala-aeto worshippers even today know him as Kande Yaka, the hunter Spirit of the Mountain. Vedahitikanda, 'The Peak Where He Was' in Kataragama, to Tamils is Katira Malai, the 'Mountain of Light' and even to this day the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā is also known in Tamil as Katira Malai Karai Yāttirai, the 'coastal pilgrimage to the Shining Peak.' In view of its strong associations with the god's origin on Mount Kailāsa, it is also well known as Daksina Kailāsa, the 'Southern Kailāsa.'

|

| Figure 1: Mount Kailāsa in western Tibet and Kataragama in the far south of Sri Lanka form a near-perfect analog to the axis mundi or susumna nadi of yogic lore. |

This long-standing postulation of a North-South axis anchored at Uttara Kailāsa in Tibet and Daksina Kailāsa in Sri Lanka takes on profound significance in the tradition of pilgrimage and mystical practice at Kataragama. For it is a remarkable fact that Mt. Kailāsa in the trans-Himalaya and Kataragama in the far south constitute a North-South axis not merely in yogic lore, but also in modern geographical terms as well (see figure 1). Coincidence or not, this fact further highlights the role of geography in Kataragama's mystical traditions.

This striking feature of a virtual North-South axis or geographic alignment between Kailāsa and Kataragama is well-known to Kataragama swamis and yogins, who regard it as a macrocosmic analog to the microcosmic susumna nadi or subtle central nerve channel envisaged in kundalini yoga. In their view, Kailāsa is homologized or equated to the thousand-petalled sahāsrara cakra, the goal of yogic practice, while Kataragama corresponds to the mulādhara cakra, the point of entry for the vertical flight to higher cakras or lokas, subtle worlds superior to our world of physical sense perception. By process of transposition, the North-South axis geographically represented by Kailāsa-Kataragama is also analogous to the vertical ray that 'shines upon the waters' in religious traditions worldwide. In this sense, the descent of Skanda-Murukan from Uttara Kailāsa to Daksina Kailāsa also represents the descent or visitation of the Spirit into matter, which expresses in metaphysical terms precisely the legend of Skanda-Murukan's disguised visitation to Kataragama to woo and wed the yearning human soul represented by Valli. In this context, the Kailāsa-Kataragama axis is also homologized to the shrine's very name Katir-Kamam, where lofty cold Mt. Kailāsa symbolizes katir (effulgence, light or brilliance, i.e. logos) while kamam (Sanskrit: kama or Greek eros) pertains to the passion of Valli and Murukan in the romantic jungle setting of Kataragama which, although undoubtedly a very human love story, is also a subtle and profound religious parable at the same time and it is on this level that scholars and devotees interpret it.

Scholars of religon, too, are familiar with this process -- in their own scholarly way, of course, if not directly and immediately as a result of actually undertaking the journey or passage as the traditions under their study may practice it. Mircea Eliade was perhaps the first modern scholar to articulate this process.10 In the context of Indian tantricism, anthropologist Agehananda Bharati describes the process as a characteristic phenomenon of tantric pilgrimage, both as a concept and as a set of observances, is the hypostasization of pilgrim-sites and shrines: the geographical site is homologized with some entity in the esoteric discipline, usually with a region or an 'organ' in the mystical body of the tantric devotee."11

These structural features of Kataragama and its legends -- which have not passed unnoticed by generations of practising kaumāra sādhakas or aspirants -- are also related to Kataragama's hoary tradition of passage to and from other lokas or worlds as well as the appearance in Kataragama of diverse spirits and godlings from other lokas. The Kataragama festival, for example, is essentially a wedding or fertility celebration which, in theory, is widely attended not only by humans but also by spirits of every hue and variety from many lokas and not just from our familiar sense world alone. Senior swamis and yogins allege that strange beings used to visit Kataragama in human or animal guise quite commonly until only a few decades ago. Such visitations have become less common, they say, due to the increasing secularization of Kataragama. As outlandish as such claims might sound at first, they should not be discarded but should be considered in the light of traditional sciences which best explain these alleged occurences on their own terms.

|

| Center of the universe in pan-Indian lore, Mount Kailāsa in western Tibet (above) is the cosmographical analog to the sahasrara cakra ('thousand-petaled lotus crown') in Kundalini Yoga and to heaven or moksha ('liberation') in soteriological terms. |

|

| The Kataragama Mahādevale on the seventh day of the annual festival gets a new pandal covering of tree branches representing its original form as a jungle shrine. |

Intertwined realms or worlds

Certain places on earth are believed to exude mystical power or s'akti partly because they are felt to be in continuous contact with their sublte counterparts in other worlds. That is, their connection with myth is sustained not so much because of a presumed historical relationship ('so-and-so came here and did such-and-such') but because the very place itself remains connected through living myths or legends that happen in principio, i.e. not at a unique unrepeatable moment in past history, but always in the eternal here-and-now (Tamil: ippo-inge).

An example of this concept concerns the Kataragama Mahadevale on the left bank of the Menik Ganga where the god is believed to reside and around which the mystery tradition revolves. The Mahadevale is a modest, single-story temple of indeterminate age said to have been originally built by the 2nd century BC Sinhala King Duttugemunu on the direct order of God Kataragama. But according to current lore, when practitioners visit the Mahadevale while in a state of yogic or lucid dreaming, they find that it has not one story but seven -- three stories above ground and three more below in addition to the ground floor. In this sense, the god's temple-palace encompasses multiple lokas and is a microcosm of the hierarchical cosmos described in pan-Indian tradition. In recent years lucid dreaming has become the object of recognised medical research worldwide, so perhaps dream researchers may some day be able to duplicate (or disprove) the findings of Kataragama's indigenous tradition of yogic dreaming.

Vows and the power of true utterances

In Kaumara tradition, vows (Tamil: nertti) and vow-fulfillment (nerttikatan) play important and even critical roles. Indeed, Valli's vow that she would marry no man but only the great god himself forms the core of the Kataragama legend and is common to the South Indian recension as well. In Sinhala folklore Kataragama Deviyo himself vows that he will remain in Kataragama always to help and protect his devotees. Murukan devotees routinely make vows to perform difficult and/or sacred acts in return for the god's arul or grace in meeting life's challenges. Both in India and Sri Lanka this takes the form of a personal promise: in return for a (usually) specific favor from a god or spirit, devotees promise to reciprocate with specific acts of penance, devotion or sacrifice.

Of course, the idea of undertaking a contract or covenant with an unseen god is not peculiar to the Indian subcontinent alone but is an honored tradition even in Semitic religions. Indeed, all over the world from remote times people individually or collectively have undertaken formal commitments or vows or covenants with unseen gods or spirits. Everywhere the practice is felt to confirm and reestablish the relationship between the human and spiritual realms by giving the force of truth to utterances and ritual acts associated with them.

In the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition too, vows play a fundamental role. The Kataragama Aesala (July-August) festival season officially begins forty-five days before the festival itself with the kap hitavima rite at the Kataragama Mahādevale when kapurāla priests go to an undisclosed location in the god's forest where they cut two tree saplings yielding milky sap and ritually 'plant' them in the public forecourt of the Mahādevale. By this ritual act the kapurālas express an unuttered vow (anirukta vrata) that they will perform the elborate Aesala festival starting forty-five days later.

On the very day that the kapuralas are performing the kap hitaveema rite, far to the north the Pāda Yātrā pilgrims have assembled at the great Vattapalai Kannaki Amman festival near Mullaittivu. Here the pilgrims make their private pledge or promise to do something which may be hard to do or else to abstain from certain habitual ego-gratifying activities, usually for the course of the pilgrimage. This may mean walking barefoot to Kataragama for some, or abstaining from smoking for the duration of the pilgrimage for others. Both are instances of 'self-naughting' or akiñcana, one of the cornerstones of spiritual practice.

Disguise and Change of Identity

Closely related to the theme of movement between lokas or spheres is the element of shifting identity. As Bryan Pfaffenberger observes, "Pilgrimage...requires the submission -- if not the annihilation -- of day-to-day identities, and emphasizes the shared experiences of the pilgrims rather than the differences among them."12 In the Kataragama tradition, this shift is a critical but gradual one that progresses over the weeks of each pilgrimage and years of repeated practice.

This process is also related to the archaic theme of divinity or majesty moving about in disguise, which is not restricted to Sri Lanka or India alone but was long common throughout the ancient world. Even today, it is recalled in the exceptional hospitality bordering upon reverence that persists in traditional oriental cultures towards guests of distant or uncertain origin, as recalled in the Sanskrit injunction atithih devo bhava: 'Regard the sudden visitor as a divinity'. In particular, the practice of traditional hospitality towards pilgrims and strangers in the form of annatānam (Sanskrit: annadāna 'offering of food') is still alive in rural Sri Lanka and has played a key role in sustaining archaic traditions like the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā. Notably, the mostly-Tamil pilgrims are served on a grand scale not only in Tamil villages but also by Sinhalese villagers along the route.

|

| Annadāna or the offering of food to pilgrims is the time-honoured basis of the Pāda Yātrā tradition. |

To this day, whether a pilgrim is a Hindu swāmi (Sanskrit: 'lord or free man') or a Muslim faqir (Arabic: 'poor man'), he (or she) carries on an inherited tradition or paramparā of divine majesty cloaked in outward poverty and simplicity. Similarly, the equivalent Tamil term āṇḍi also encompasses both paradoxical senses of lordship and poverty; the term is especially characteristic of Skanda-Murukan and the initiates of his cult.

In the mythos of Kataragama, Skanda-Murukan does not display his divine nature openly from the start but approaches Valli Amma and her relatives in a series of disguises. Kataragama-Skanda in particular is regarded by his Tamil devotees as kaṇḍaḻi, God as the Supreme Identity, i.e. formless. Therefore whatever form or 'face' the god chooses to show is only a guise. In Tamil literary and oral traditions, Murukan appears to Valli first as a handsome young hunter in a brazen bid to tempt her to violate her vow, as it were. When this bid fails (but succeeds in the sense of testing her vow), he tries other disguises and finally wins the trust of Valli and her clan by appearing in the pitable guise of a old hunchback 'holy man.' Because of his use of cunning and disguise to get near to Valli and elope with the girl even when she is closely guarded by her clan, the Kataragama god is widely regarded as a wily rogue and a 'thief,' albeit a beneficent and honorable one. Interestingly, this notion of the beneficent solar deity Skanda being a rogue is traceable to as ancient a canonical text as the Atharva Veda, wherein a section called the

|

|

At that moment, Murugan invoked the help of his brother Vināyaka who appeared behind Valli in the shape of a frightening elephant. The terror-stricken girl rushed into the arms of the Saiva ascetic for protection. Painting from Tiruttani Devasthanam. |

In the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition also, initiates essentially follow in the footsteps of their roguish god and his followers before them. Leaving behind their normal identities in the villages from which they come, these 'ordinary villagers' become eccentric swāmis and swāmi ammas -- trusted counselors, teachers and healers whose reputation waxes with the number of Pāda Yātrās undertaken and the distance they have traversed from their home village. Of course, this also raises suspicions about the 'real' character of the pilgrims, who as 'messengers' of the god are expected to remain (at least temporarily) celibate, vegetarian and high-minded. Of course, many fall short of the ideal. What is significant is that an age-old Dionysian tradition of a wily fertility divinity coming in disguise still survives, if only in Sri Lanka since these elements are hardly evident in South India. Not surprisingly, the theatrical element (often as pantomime) too survives in association with these standard elements of disguise and protean identity. This again is entirely in keeping with the character of a deity who relates to humanity through play-like activities that fully deserve the appellation 'mysteries.'

Reversal of time and causation

Mystical traditions worldwide allude to the desirability of remaining in, or returning to, the state of childlike wonder and innocence. But in kaumāra sādhanā in particular, the quest has special resonances with a god who since remote antiquity has been invoked primarily by names (Murukan, Sanatkumāra, etc.) implying perpetual youth. Kaumāra sādhakas undertake a deliberate course of practices that aim to reverse the course of mental and physical aging -- in effect, 'reversing the course of the Ganges' and turning the irresistible flow of time and causation backwards towards its origin in principio. This in part explains what appears to the non-participant observer to be backward or topsy-turvy logic that characterize many 'impractical' cult practices such as walking great distances when cheap transport is easily available. Hence, too, the natural affinity of works like Alice in Wonderland to the practice and exegesis of Kaumara traditions.

In the context of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā, time reversal is evident to discerning pilgrims not only inwardly but even outwardly as well. The pilgrimage customarily begins from one's own doorstep or wherever one happens to be when one gets an irresistible 'call' to attend the Kataragama festival as testified to this researcher by many Tamil, Sinhalese and Muslim pilgrims. It therefore begins for most pilgrims from relatively developed and ordered communities within the framework of contemporary Sri Lankan society. But as the pilgrims move southward, they progressively leave small urban centers behind; the towns and villages get smaller and farther apart until they pass the last small village of Panama, after which they must cross nearly a hundred kilometers of uninhabited jungle -- Yala National Park and environs. In effect, the pilgrims are moving backwards in time from the twentieth century to a prehistoric era until finally at Kataragama -- prepared by weeks of mental adjustment and 'walking meditation,' in theory at least they have entered the 'real' Kataragama in its primordial identity as a mythical cult center, entirely above and beyond time, causation and history.

The Narrow Gate: Pilgrimage and the Passage to the Otherworld

The storytelling tradition of Kataragama speaks of secret or hidden passageways leading to and from other lokas or realms. Typically the tradition speaks of passages that lead underground, rather like Alice when she tumbles into an enchanted rabbit hole. While the possibility of discovering such gateways cannot be discounted entirely, the passage referred to is allegorical in character yet intensely real to one who undertakes the journey. With help from experienced wayfarers, the seeker studies the surface contour of his or her own immediate realm of ideation and perception. At moments of insight, habitual patterns of ideation and perception cease and older (yet fresh and new) modes of ideation present themselves. When this happens, the sadhaka percieves the world in strange and magical new ways.

The perilous passage through an Active Door or 'narrow gate' is' a common motif of folklore traditions worldwide and has been the subject of a vast literature, of which Ananda Coomaraswamy's essay "Symplegades" is arguably the best.14 His description of the hero who undertakes the Grail Quest also captures the essential character of the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition:

The expert, for whom the antitheses are never absolute values but only the logical extremities of a divided form (for example, past and present of the eternal now), is not overcome by, but much rather transits their "north-and-southness" or, as we should say, "polarity," while the empiricist if crushed or devoured by the perilous alternatives (to be or not to be, etc.) that he cannot evade.15

The essential story of the passage between 'Clashing Rocks,' according to Coomaraswamy, is replete with the "signs and symbols of the Quest of Life which have so often survived in oral tradition, long after they have been rationalized or romanticized by literary artists."16 "The distribution of the motif," he adds, "is an indication of its prehistoric antiquity."17

The Kataragama Pāda Yātrā, too, consists of folk tradition practices and legends which suggest that, although preserved and transmitted by generations of simple villagers, it was originally undertaken and its possibilities developed by religious specialists of considerable doctrinal sophistication. The 'folk' character of the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā tradition, therefore, properly refers only to the custodians who have preserved it.

|

| Above at left, Muttukumar Vel Swami (d. 1996), veteran of over fifty Pāda Yātrās since the 1930's. |

|

| Kataragama Pāda Yātrā, once a male preserve, is now largely in the hands of senior women, called swāmi ammas. Bebi Amma at right. |

Kataragama Pāda Yātrā: Present and Future

Who are the Pāda Yātrā pilgrims? As a proportion of the Tamil Hindu population, they are a small minority. After a decade in eclipse, a high proportion (nearly half) of Pāda Yātrā pilgrims today are novices, but many others have walked not once but repeatedly, although the practice takes weeks or even months to perform, depending upon from where one starts. Many senior pilgrims report that they first walked as children in the company of one or both parents. A case in point is that of Mrs. P. Maheswary of Trincomalee, who first walked with her family as a teenager in the 1950's. Bebi Amma (as she is now known) has since walked nearly forty times from Jaffna or the farthest starting point from Kataragama (currently Trincomalee).

When the writer first walked with the Pāda Yātrā pilgrims from Jaffna in 1972 in Bebi Amma's party (the Celva Canniti kuttam) she was already a seasoned veteran. Today she is the most senior pilgrim (seniority is reckoned not by age but by the number of Pāda Yātrās). As such, despite her gender, Bebi Amma has inherited the role of Vel Swami, the ritual bearer of the vel or spear-emblem of Skanda-Murukan and group leader who decides (or confirms collective decisions) upon such issues as the route (critical in dense jungle where even experienced pilgrims may easily get lost), where to halt and when to start, etc. The previous Vel Swāmi, Muttukumar Vel Swami of Kilinochi, had walked from Jaffna in excess of fifty times since the late 1930's, possibly an all-time record. In times of peace, the pilgrims used to walk in small kuttankal (parties) consisting of as many as thirty (the maximum capacity rice pot that one adult can carry). But nowadays for reasons of security a kuttam may consist of up to 170 adults and children, an unwieldy size considering that the party is but a loose, temporary organisation -- and yet life-critical decisions must be made and executed daily, often in remote dry jungle.

The total number of pilgrims is also difficult to ascertain, since pilgrims walk of their own acccord whenever and by whatever route they please and only recently have Sri Lankan security officials begun to try to register the foot pilgrims as they arrive out out of the Yala National Park to attend the Kataragama festival. Hausherr cites a rough figure of 1300 Pāda Yātrā pilgrims from Jaffna district alone in his study in the 1970's, which tallies with estimates this researcher heard elsewhere in the early 70's.18 Following the anti-Tamil riots of 1983, for years it was not safe for Tamils to walk openly through Sinhala areas, and since 1990 they have not been able to walk from points north of Trincomalee. But with the founding of the Kataragama Devotees Trust in 1988 with the explicit objective of reviving the Pāda Yātrā and other Kataragama traditions, the number of pilgrims has begun to return to earlier levels, if only in Sri Lanka's eastern districts. The great majority of foot pilgrims walk from Batticaloa and Ampara districts, which are much closer to Kataragama than Trincomalee, Vavuniya or Jaffna districts where only the most ardent devotees are prepared to walk for forty days or more. Some villages in Ampara district are less than a week's walk from Kataragama, such that farmers can afford to leave their fields for a short time and return within ten days or two weeks at most, which villagers in more distant districts can ill afford to undertake.

Significantly, the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā has continued to include one or more Western pilgrims each year as well as a few Sinhalese devotees despite the elements of risk and hardship involved. Indeed, it would be wrong to characterize the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā solely as a Tamil Hindu tradition, although Tamils have long been considered as the its custodians and have long been predominant numerically as well. The survival of this ancient yet vigorous tradition despite all the challenges posed by Sri Lanka's changing society suggests that it may continue to flourish in spite of rapidly changing social conditions. While its precise impact upon Sri Lankan society in return has never been studied, the tradition has undoubtedly helped in establishing inter-ethnic harmony and respect in years past and could play an important future role in healing the wounds of long years of ethnic strife.

Despite the shroud of secrecy surrounding the ancient Kataragama god's cult, nevertheless there are certain injunctions or guidelines based upon longstanding tradition which are common knowledge to experienced pilgrims. Important ones pertaining to the Kataragama Pāda Yātrā may be summarized as follows:

- Be alert to the Spirit's inner and outer messages. If the 'call' comes, heed it.

- Do not announce your destination or starting time. Upsets may occur.

- Maintain a low profile. Learn from others who know more than you know.

- Increase the faith all around for self and others. Or else remain at home.

- Keep your promises few and simple, but keep them. Penalties can accrue.

- Sleep out of doors at night or in temples, but not in private homes.Taste the homeless life fully and enjoy it while you can.

- Accept whatever comes. Blessings may appear in disguise.

- Share whatever comes; accept the alms, friendship and wisdom of others.

- Do not unload your personal grievances upon others while en route. Deliver all complaints to Kataragama and register them there personally.

- Trust in the Spirit and make it your constant guide. Beware of imitations.

In summary, an age-old Sri Lankan mystical tradition closely associated with archaic concepts of sacred geography still survives among simple and doctrinally unsophisticated villagers whose inherited practices may be characterized as raw bhakti or devotion, yet who are aware of many elements of the profound doctrine upon which their practices and beliefs are based. Seen in this light, it should be clear that Kataragama and its associated Pāda Yātrā traditions preserve many features of great antiquity that deserve to be appreciated on their own terms, including elements of an archane traditional science of cosmography or sacred geography which have long escaped the attention of outside observers. As such, this study should be regarded only as an initial survey of a subject to be examined appropriately and in greater depth that it richly deserves.

Notes

1. Tamil: Karuttilirukkum katirkamattunai en tedukindray?

2. Even haj, one of the Five Pillars of Islam, is incumbent only upon those Muslims who can afford to undertake it.

3. see Gananath Obeyesekere, "The Fire-Walkers of Kataragama: The Rise of Bhakti Religiosity in Buddhist Sri Lanka," JAS, 37 (1978), pp. 457-476 and Bryan Pfaffenberger, "The Kataragama Pilgrimage: Hindu-Buddhist Interaction and its Significance in Sri Lanka's Polyethnic Social System," JAS, 38 (2) 1979, pp. 252-270.

4. Tiruppukal Mantani, (New Delhi: Tiruppukal Anparkal, 1991), pp. 547-558.

5. anonymous, Saint Yogaswami and the Testament of Truth, (Jaffna: Sivathondan Society, 1972), pp. 122,140.

6. extensively documented by Klaus Hausherr in "Kataragama: Das Heiligtum im Dschungel Sudost-Ceylon aus geographischer Sicht," Buddhism in Ceylon and Studies on religious syncretism in Buddhist countries, ed. by Heinz Bechert (1978), pp. 246-260.

7. published in English as Kataragama: The Holiest Place in Ceylon, trans. Doris Pralle, (Colombo: Lake House, 1966).

8. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, "Symplegades" in Studies and Essays in the History of Science and Learning Offered in Homage to George Sarton on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday (new York: M.F. Ashey Montagu, ed., 1947), reprinted in Coomaraswamy, ed. Roger Lipsey (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1977) Vol. I pp. 521-544.

10. Mircea Eliade, Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries: The Encounter Between Contemporary Faiths and Archaic Reality (London: Hervill Press, 1960), pp. 125-55.

11. Hans-J. Klimkeit, "Spatial Orientation in Mythical Thinking as Exemplified in Ancient Egypt: Considerations Toward a Geography of Religions," History of Religions, Vol. 14 No. 4 (1975), pp. 267-271.

12. Mircea Eliade, Le Yoga: Immortalite et Liberte, Paris 1954. English version trans. by W.R. Trask, Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, (New York: Bollingen Series, Pantheon Inc., 1958) p. 198.

13. Agehananda Bharati, The Tantric Tradition, (London: Rider & Co., 1965), p. 90.

15. Paris'istas of the Atharvaveda, ed. Bolling and Negelein: 1909, pp. 128-35, cited in Asim K. Chatterjee, The Cult of Skanda-Karttikeya in Ancient India, (Calcutta, 1970), pp. 4-5.

This article first appeared in The Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies, Vol. XV No. 2 March 1998, pp. 33-52. It also appears in Kataragama: The Mystery Shrine (1998).

Patrick Harrigan (M.A., University of Michigan) studied sacred geography and allied subjects under the tutorship of German Swami Gauribala from 1971 until German Swami's samādhi in 1984. In 1972 he walked Pāda Yātrā from Jaffna to Kataragama with German Swami and since 1988 he has walked annually from Trincomalee as the Kataragama Devotees Trust's Pāda Yātrā field representative. Since 1989 he has been acting editor of the Kataragama Research Publications Project.

Download this illustrated article as a PDF file (1 mb)

| Living Heritage Trust ©2021 All Rights Reserved |