|

| |||||||||

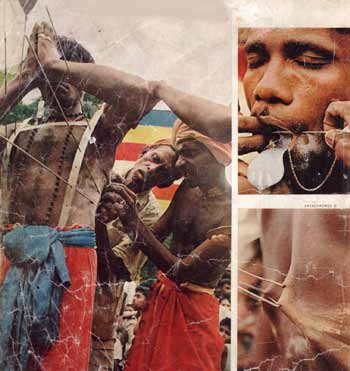

A Vow to Walk the Fiery PathExtracts from The National Geographic April 1966 article "Ceylon" by Donna K. and Gilbert M. Grosvenor, pp. 479-486. We had just reached the De Mel home when Dan telephoned. He told me, excitedly, "I have learned of a fire-walking ceremony in Kolonnawa village, near Colombo. Before the ceremony, a man named Mohotty will pierce his body with needles and pull a cart roped to hooks in his back." Now it was my turn to be excited, if a bit skeptical. Hurriedly I gathered up my camera gear, and we piled into Dan's car for the short drive. From the main road we heard lively flutes and drums resounding from the small courtyard of a village house. Fronds of margosa, the tree of purity, decorated doorways; coconut flowers, alms to the Hindu God of Kataragama, adorned the doorstep of the house, and Buddhist flags of brilliant blue, yellow, red, white, and orange flew from ropes strung around a small shrine laden with fruit and incense (page 479) "Why do they fly Buddhist flags at a Hindu ceremony?" asked Donna. "Madam, many Buddhists take part in Hindu ceremonies of piercing and fire walking," explained Dan. The Hindu deities for these rites, Vishnu and the God of Kataragama, are recognized by Buddhists, and Hindus in turn pay homage to the Buddha." A tall, fragile-looking man with soft, calm eves appeared and introduced himself as Mohotty. Anticipating our questions, he explained: "I walked the coals in devotion many times as a young man, but when my father was falsely accused of murder, I vowed that if he was found innocent, I would reconfirm my faith each year by walking the fiery path and enduring the needles. This I have done ever since he was freed 16 years ago." Mohotty's words sent my eves searching his face and body for puncture scars. Not a mark could I find. Suddenly, drums pound a faster rhythm, and the villagers crowd closer as ten dancer, thrashing their heads violently from side to side, whirl around the courtyard. The dancers kneel, and Mohotty rubs their checks, arms, and chests with sacred ash. They stare with glazed, half-closed eyes, bodies motionless, as Mohotty forces skewers through each man's cheeks. Not a drop of blood seeps from the wounds, nor is there any expression of pain. Mohotty Submits to Steel and FireThen steel pierces Mohotty's own cheeks; needles drive into his arms from shoulder to wrist; tiny arrowheads sink into his chest and stomach; spiked clogs are lashed to his feet. Straining, three men drive fearsome hooks into Mohotty's lower back, but only once does he sway, as if faint. He seems coherent, but lost in utter supplication to his gods. Ropes attached to the cart and tied to hooks in Mohotty's back pull taut against stretching flesh. Slowly, he draws the creaking cart around the courtyard. We gasp. Children, wide-eyed, reach for their mothers' hands. Only Mohotty remains expressionless. "What is your secret?" I question him later. "My secret?" he repeats. "Faith, total faith in my gods. Now, if you'll excuse me, I will enter my little shrine to pray." A great fire smolders until long after midnight, when charting dancers, gleaming with perspiration, circle the red embers. One man collapses; others drag him away. At 4 a.m. my friend Ed Lark, an American movie photographer and lecturer, measures the temperature of the coals with an optical pyrometer from the Ceylon Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research. The pyrometer registers 1,328° F. Since Ed is also a trained engineer familiar with this precise instrument, I trust his measurement. Crowds perching on banks fall still as a young man dances across the 20-foot carpet of coals, twisting his body and feet as he moves (page 483). Then another man follows, scooping up handfuls of embers and throwing them over his shoulders. Nearly twenty men, women, boys, and girls fire-walk, not once, but two and three times. Mohotty crosses the fire four times, twice with his young son on his shoulders. The crowds chant, "Haro-hara!" When it is over, we rush to thank Mohotty for letting us photograph the ceremony. Smiling, as if reading our minds, he sits and lifts his feet. They bear no trace of burns or blisters. Well after dawn we fall into bed, but sleep evades us. Our minds cannot digest the incredible sights we have witnessed, nor can we explain them by hypnosis or drugs, tricks or gimmicks. What we saw was real, as real as the faith upon which these believers base their immunity from pain of steel or flame. Editor's note: Contact information: 9, Vijayapura Kolonnawa, W.P. Sri Lanka Tel: +94 77-627-9152 or +94 77-906-1963 or +94 71-635-0309 or +94 77-914-8178 Or e-mail: kataragama@gmail.com |