|

| |||||||||||||||||||

Kataragama Skanda: A God for All Seasons

By Jennifer Henricus

|

| The annual Kataragama festival, which honours the Hindu god Skanda, brings together Sri Lankans of all faiths. |

Pageantry, ceremony and ritual are part of everyday life in Sri Lanka. No matter when you visit this isle, you're bound to be caught up in some form of national celebration. However, visitors to Sri Lanka in the latter part of July and early August will be fortunate to witness two of the country's most spectacular pageants: the Kandy Perahera and the Kataragama festival. Both are centred around the Esala full moon poya, which falls in July or August.

The Kandy Perahera, the more famous of the two, is held in the ancient hill capital of Kandy, transforming this picturesque city into a maelstrom of colour, light and milling humanity as the sacred tooth relic of the Buddha, perhaps the most venerated object of Buddhist iconology, is taken in procession around the city.

The Kataragama festival is awesome and fascinating in a different way. Unlike the grand spectacle of the Kandy Perahera, which is a staged visual treat of dancing, drumming and the slow parade of 100 caparisoned elephants, the Kataragama festival is a spontaneous procession of devotees whose feverish worship of the Kataragama god, Skanda, makes it an unforgettable experience.

Pilgrims, however, will warn you that the festival is not for the faint-hearted. The whole festival is mainly of self-mortification to fulfill vows and repay the god for favours granted. Thus, the penances might shock those uninitiated in the Hindu ritual of worship.

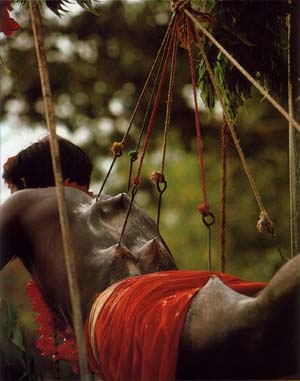

These penances range from minor acts to near fatal ones. Some roll half-naked in the scorching sands around the precincts of the temple, while others have their cheeks and tongues pierced with small spears or have sharp hooks embedded in the upper torso of their bodies. The more daring and religiously devout take part in the famous fire-walking ceremony — treading on scorching embers in utter faith and devotion — and the legend is that only the unbelieving get burnt. Most do not even show a blister.

The holy sanctuary of Kataragama and its venerable festival are as old as civilization itself in Sri Lanka. Some insist that the sanctuary is even older than the Sinhalese race, whose origins go back to the 5th century BC. Others say the sanctuary originated when Buddhism came to Ceylon a century later.

The sanctuary nestles on the banks of the Menik Ganga (‘Gem River') close to the Yala wildlife reserve, in the deep southeast. Until very recently, Kataragama was a small jungle village with a dirt track leading from the town of Tissamaharama, 19 kilometres away. Kataragama's metamorphosis came with the construction of a motorable road and the introduction of electricity and a steady supply of water to the area. It is now a bustling town constantly crowded with pilgrims and hordes of vendors with their colourful wares.

Since the route from Colombo runs along the picturesque south coast, the journey today to Kataragama is a pleasant one. It's easy to stop en route to cool off in the sea, or to lie on a deserted golden beach. Less than a century ago, however, the journey was arduous and hazardous, so much so that pilgrims made last wills, bid adieu to friends and family, and never expected to return. In fact, some did not. But death on such a journey was thought to be a sure passport to heaven.

Although Skanda, the god of Kataragama is a Hindu god, he is worshipped not only by Hindus but also by Buddhists, Muslims and even a few Christians. To the Hindus, the sanctuary might be their most sacred shrine. It is said to form the southern point of the axis along which both great sanctuaries of the Hindus lie, the other being the holy mountain of the gods, Kailasa, in southern Tibet.

The history of Kataragama goes back hundreds of years, the legends thousands of years. As German historian Paul Wirz wrote, "It is difficult to decide today which of all the traditions are based on historical fact and which are free inventions and poetic license....So hazy and contradictory are the records about the origins of the sanctuary that it is now impossible to separate historical facts from legendary stories."

The most famous legend of Kataragama is in the epic Sanskrit poem Skanda Purana, which dates back to the 5th century BC, although a Tamil version of the poem is said to have been available in the 8th century BC. The legend has it that Skanda — also known as Kanda Kumara and the second son of Lord Siva, who was the highest god among Hindu deities — came from India to Kataragama when he heard of Valli Amma, an exceedingly beautiful girl who lived in the jungles of Kataragama. Valli was the daughter of a doe mother and hermit father, and had been adopted by a Vedda (aboriginal) chieftain.

Skanda came in search of Valli in the guise of an old beggar and asked her for food, drink and her hand in marriage. The first two she gave him but turned down his offer of marriage. Just then an elephant came crashing out of the jungle and frightened her. It was Skanda's elephant-headed brother, Ganesh. The two had planned the escapade to persuade her to marry Skanda. Skanda saved her from the elephant and in gratitude she agreed to marry him. This incident is said to have happened at what is today known as Sella Kataragama, and a temple dedicated to Ganesh is situated here.

Skanda soon transformed into a young man and the couple were married and lived on Kataragama peak, or Vedahiti Kanda ("The Mountain Where They Stayed"), one of the Seven Hills of Kataragama. However, there was a hitch. Skanda already had a wife, Deva Sena, or Thevani Amma. When she heard of his second marriage, she was jealous and angry. She came with a retinue to Kataragama and persuaded the couple to come down from their hill and live with her. They complied and the three lived happily ever after. As the power of the deity filled the area, the Veddas and others in the area started venerating Skanda and his wives.

The millions of pilgrims who visit this holy shrine treat old men, especially beggars, with great respect (one can never tell if one of them is the god in disguise). In fact, the festival is a unique happening because in this two-week period, people put aside earthly prejudice of caste, race and creed and are united as one. As Richard Spittle wrote of the festival in 1933, "One is struck by the camaraderie that prevails; caste and class distinctions have been forgotten and pilgrim greets pilgrim with the immemorial salutation, 'Haro Hara'." ("Haro Hara" is a mantra used to invoke the god Skanda.)

This year (article written in 1988) a special national effort at unity and peace will be attempted with the centuries-old pilgrim walk from Vallipuram in the northern Jaffna peninsula, down the east coast, and through the jungles of the Yala National Park to Kataragama. Thousands of devotees are expected to take part in this walk, which starts at the beginning of June and takes about 45 days.

Pilgrims, especially the Hindus, attend the festival only if they get a calling from the god. Several weeks before the festival, they start fasting and praying. When they get a distinct ‘urge' to go, they leave without much fanfare, believing that they will return only if the god so wishes it, as one devotee put it.

The Kataragama sanctuary itself is composed of a series of devales, or temples, and the famous Buddhist dagoba, the Kiri Vehera. If one expects to find the usual grandeur seen in temples of this period, they will be disappointed. "There are no grand edifices here such as its renown would lead one to expect," wrote Dr Spittle in his book Far Off Things, "but merely crude buildings devoid of the least architectural pretensions....There is, however, a solemnity about them denied to finer temples."

What's remarkable is that the shrine has no image of the god Skanda — only a painting of him on his peacock mount, and his two wives, Valli Amma and Thevani Amma, on a curtain in the Maha Devale (Great Temple) which, together with six other curtains, shrouds the sacred relic, or yantra, of the god.

The yantra is the centre of the shrine's rituals and festivals. Every night during the two weeks of the Esala Perahera, the relic is brought out of the Maha Devale by the high priest, or kapurala, and is borne on an elephant to the temple of Valli Amma. The mystical symbol is then placed in the temple behind a curtain, where it remains to allow the god to refresh himself in the company of his favourite wife.

Some devotees celebrate their marriages at Kataragama, spending their wedding night at Sella Kataragama, where Skanda and Valli were wed — all in the belief that the god will bless them with eternal wedded bliss.

|

|

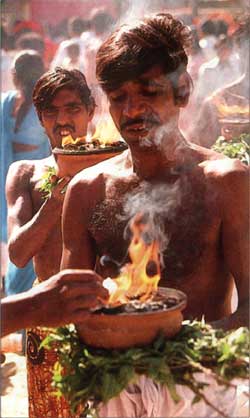

The celebration itself is alive with colour, light and sound. As the multitudes follow the caparisoned elephants to the chants of "Haro Hara," the drums throb, the pipes shriek, the conch shells moan and the bells chime. Devotees bearing semi-circular kavadis on their shoulders dance in worship of the god, while others perform their acts of penance. The night air becomes filled with dust and the fumes of camphor burning in vessels carried on the heads of the devotees. The whole scene has a mystical, trance-like atmosphere cast over it.

"It is a marvelous tableau...a fantastic drama of human life that has been ordained by a powerful god," said film director Manik Sandrasagra, who recently made a documentary film of the festival. "It has everything: mystery, action, solemnity. It is a spontaneous pageant."

On the night of the full moon, which marks the finale of the pageant, one can witness what Dr Spittle calls "the greatest thrill in that place of thrills": the fire-walking ceremony.

After the night's perahera, an area is cleared in front of the Maha Devale and spread with huge bundles of tamarind firewood, the embers of which last longer than any other. The wood is lit by the kapurala after he has invoked Agni, the god of fire. At dawn the red-hot cinders glow over an area measuring four by two metres, and are ready for those who dare this penance. They are not many and they do not undertake it without a rigid fast, long meditation on the god and fervent prayer. At about three a.m., when the full moon is very bright, they bathe in the Menik Ganga and in wet clothes go to the Maha Devale to worship. Then standing before the embers, they pray to Agni and as chants of "Haro Hara" rise from the spectators they tread the glowing path.

Rarely are there casualties. However, sometimes amateurs recklessly attempt the deed and get severely burnt. Dr Spittle records that tragedy struck the day he visited: "One unfortunate fellow, determined to outdo the rest, attempted walking through, saddled with a kavadi. He had gone a few yards when he fell and was so badly scorched before being rescued, that he died soon afterwards."

Later in the day, the festival is brought to a close with a "water-cutting" ceremony. The high priest takes the holy yantra to the river in procession and in a special enclosure draws a magic circle in the riverbed and strikes the water with a sword or rod. The casket bearing the holy relic is then immersed in the water, and a frenzy of music and chant burst forth from the devotees as they plunge into the sacred waters, confident that their sins will be cleansed.

Some women devotees offer gold ornaments to the god. They clip the gold onto the gills of fish living in the river and urge them to take it to him. But sometimes the god shares these offerings with the less privileged as bathers discover fair amounts of the precious metal. "Haro Hara...the god be praised!"

| Note: First-time visitors to the shrine should remember to remove their footwear before entering the precincts of the temples and to be properly clad. |

| Accommodation in Kataragama is difficult to come by at the height of the festival, even though there are several good rest houses and hotels in the area. It is therefore advisable to make reservations in advance, or stay at Tissamaharama. |

Courtesy: Serendib Magazine, Vol. 7 No. 3, May-August 1988

|