Tall Tales and Deep Truths

Since remote prehistory, island Lanka has been celebrated far and wide as the setting for incredible tales of legendary beauty, wisdom, and magical enchantment. Her lush tropical climate and breathtaking landscapes appear to enhance the human imagination like few other places on earth. What, then, is it that moved ancient people to speak so highly of island Lanka?

Early Arabic mariners, for instance, believed that in Lanka or Serendib they had re-discovered the original Paradise or Garden of Eden. Many of them, unsurprisingly, decided to remain in Serendib as the forefathers of the island's Islamic community. Long before that, however, Lanka's reputation for the marvelous had already spread far across the ancient world.

Storytelling

The ancient art of storytelling (Sanskrit: iti-hasa 'thus-told') is highly regarded in traditional cultures where it is often the principal vehicle for the transmission of in-depth understanding as opposed to the mere accumulation of bits of information. Many anonymous storytellers have spun or woven tender songs and thrilling stories sung in spontaneous verses of ecstasy, while others have enacted mute pantomime performances offered up to the divine Source of their inspiration.

A good story, after all, is both entertaining and instructive at the same time. Moreover, it may be told and retold in any number of ways. And stories may serve as bridges of understanding between people, for a good story may be enjoyed and appreciated by young and old or rich and poor alike, each according to his or her own level of appreciation.

Storytelling was developed into a fine art in ancient Lanka, and to this day the principles of storytelling are still being handed down lovingly from one generation of storytellers to another as a parampara (Sanskrit: 'from another to another'). Even today in an age of radio and television broadcasting, traditional storytelling is still very much alive as it grows and changes to meet the challenge of changing times. From the anonymous masters of the past to modern storytellers such as Arthur C. Clarke, all have found island Lanka to be source of inspiration, a paradise for visionaries.

|

|

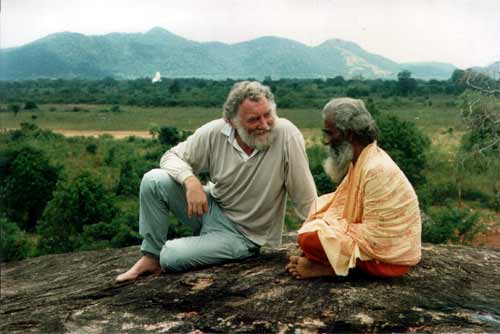

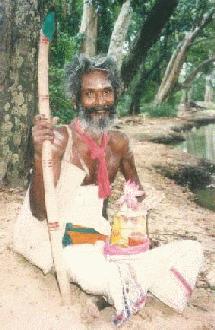

Dr. David Bellamy meets Kataragama's Matara Swami: Storytellers learn from other storytellers. Background: The Seven Hills of Kataragama.

|

Sunken Lanka

One example of a recurrent storytelling motif that appears and re-appears under various guises is that of characters or even whole kingdoms that are said to be 'sunken' or gone 'underground' and which may periodically re-surface only to disappear again. Such stories are known the world over, or course, but in Lanka they have been developed into a fine art.

The 'original' Lanka is said to be mostly submerged, like an iceberg. In remote antiquity, we are told, Lanka or Lemuria as some call it was a continent that was home to brilliant civilization of exceptional spiritual vitality, but which later catastrophically sank beneath the waters except for the small portion that is Sri Lanka today.

Ptolemy of Alexandria, the 2nd Century AD 'Father of Modern Geography', and other ancient geographers consistently reckoned Lanka or Taprobane of their time as being many times greater than the island known to geographers today. Was it really so, or was Taprobane larger only in the imagination of those who saw it or heard of it?

It is problematic, to say the least, for scholars to accept such accounts at face value in the light of what recorded history and modern geology tell us. However, when one bears in mind that these tales were articulated and transmitted to us by successive generations of village bards, minstrels and other storytellers stretching back from hoary antiquity, whole new dimensions of understanding begin to emerge.

Methodology

In order to read and decipher the subtle messages encoded in allegory and metaphor, one must employ the same tools or principles that were used to encode them. Cryptic tales may be storehouses of uncanny yet practical wisdom for those holding the key to unlock the human heart's unlimited capacity for exuberant creativity. The brilliant tropical setting of Sri Lanka, it would seem, has long served as both catalyst and stage for a vast cosmic dream or drama that continues to unfold even today.

Peacock Ravana

In other words, traditional storytellers wove fact and fiction together as the warp and woof of a single, all-inclusive fabric of reality. Again, dedicated connoisseurs of the art may also unravel life's great puzzles in the course of time. What, then, are scholars or lay people to make of these persistent legends of sunken continents or underground kingdoms?

Fortunately, Sri Lankan lore and legend is replete with related imagery and details describing worlds parallel to ours.

For instance, one persistent legend preserved in Tamil speaks of Patala ('Sunken) Lanka, a parallel-dimensional Lanka far 'underground' where mighty King Ravana's powerful elder brother Mayil ('Peacock) Ravana slumbers in repose until his parallel-dimension 'brother' Ravana himself descends to waken the sleeping giant and enlist his support in a mythical or magical war being waged upon the surface of Lanka.

Other related motifs speak of Yaksas ('spirits'), a class of powerful human-like beings who once ruled all of Lanka before withdrawing into the shadowy jungles and caves where they are still said to brood as invisible spirits that may emerge at times from within the human mind itself, as it were.

Perhaps the best-known and yet least-understood example of this storytelling motif concerns Kataragama, the sylvan shrine complex and fabled source of wisdom, grace and enchantment for millions of Sri Lankans from remotest prehistory down to the present age. The Kataragama god, known as Kande Yaka, Skanda, Murukan and a host of other names, is the sole deity common to the Vedda, Sinhala and Tamil pantheons. In the twentieth century, Sri Lankans of all communities have been drawn to his various shrines in ever-greater numbers, 'voting with their feet' in mute testimony both to Kataragama's swelling popularity and to his unquestioned power and generosity.

Storytelling schools or sampradayas of the indigenous Wanniyal-aeto, Sinhala and Tamil communities all agree in giving prominence of Kataragama. Even today fresh tales of Kataragama continue to surface on a regular basis.

The ever-youthful and ever-mischievous Spirit of the Mountain, Kande Yaka, and his jungle sweetheart Valli, so we are told, still frolic in Kataragama in various guises and dis-guises. Even today, they are said to be still as fond of playing such games as 'hide-and-seek' with one another and with like-minded devotees as they were thousands of years ago. Whether ancient or modern, the stories of Kataragama typically abound in elements of play, disguise, secrecy, and surprise, all handy qualities that one might reasonably expect of a shape-shifting child-god such as Kataragama-Skanda.

Wonderland

Equally intriguing are stories passed down by Sinhala and Tamil-speaking swamis, widely believed in Kataragama, that beneath the surface Kataragama known to most people there exists a secret, hidden or parallel Kingdom of Kataragama. Even today there are respected swamis who commonly speak of Kataragama as an 'underground university' complete with its own departments, faculty and students. This underground Kataragama is an initiatic institution that once operated on the surface but which, like the yaksas of olden days, withdrew into a shadowy realm where their arcane knowledge could survive to emerge later at a suitable time.

Many of Kataragama's stories stretch not only credibility but the human imagination as well. Some tales still circulating tell how unsuspecting seekers, similar in many ways to Alice in Wonderland, may stumble across magical thresholds or gateways and tumbled headlong into topsy-turvy worlds of paradox, mystery and enchantment. Few who cross through these invisible trap doors ever return at all, and those who do return are often regarded as mad for life. Very few who venture into the otherworldly labyrinth or maze of Kataragama ever return as the same person who departed.

Hidden Kingdom

Whatever the entertainment value of the uncanny tales of Lanka, the storytelling paramparas themselves urge us to search beneath the surface meaning for a deeper meaning veiled in allegory and metaphor. On this level, there does indeed exist a working (or, rather, playing) Kingdom of Kataragama with its tender Lord Kumara Swami himself presiding as its unseen Lord of Hosts.

Even today, royal court rituals of inestimable antiquity are routinely re-enacted in Kataragama, for the pujas and processions there are precisely divine court rituals. The present system of five hundred and five rajakariya ('royal service') roles is still very much operative and virtually intact more than two thousand years after it was formalized by King Dutugemunu in the second century BC. This is truly a marvel of social engineering which space scientists and engineers ought to investigate to develop fail-proof systems that can remain functional without need of maintenance for centuries at a time.

Indeed, the whole of Kataragama presents itself as a surviving model kingdom that keeps running smoothly on 'automatic pilot', as it were, regardless of whether the reputed god-king is present there, or not. And as for the underground 'University of Kataragama', it too still has its place in the shadows along with its humble yet earnest faculty and students who preserve and transmit the ancient esoteric lore in new guises. But only those who 'dig' beneath the surface of Kataragama may dis-cover its multiple dimensions. And as for the types of research that take place in such an underground university, one can only speculate or else venture to find out for oneself.

Low Profile

Seen in this light, these legends of the submergence of island Lanka or Lemuria, once so lightly dismissed by scholars as mere fairy tales, are seen to encode ancient pragmatic wisdom, leaving a broad trail of scattered clues for anyone willing to 'dig' for patterns of deeper meaning beneath the surface meaning of Lanka's haunting tales of entertainment and wisdom combined.

Perhaps, then, the original Lanka or Serendib or Lemuria, like Kataragama, has never really gone anywhere, but has only been lost from view by modern-educated people who find it difficult to accept that such a place and such a living tradition ever existed at all. If so, then a great deal remains to be discovered about legendary Lanka's fantastic wealth, technology and arcane knowledge.

Like Kataragama, it seems that the original magic and enchantment of island Lanka have survived by maintaining a low profile and by adapting unobtrusively to the needs and perceptions of a materially-fixated world blinded by its own incomprehension of worlds or modes of thought that are, to the majority of people today, unthinkable. Like the chameleon that takes on the color of its surroundings, the original enchantment of Lanka lives on precisely because it has escaped the ravenous attention of modern predatory civilization. The rumors of its demise merely serve to deflect profane scrutiny.

The world's greatest stories have their roots in truth, and the greatest storytellers have always insisted that they speak only words of truth. If there is only half as much truth to all these stories as the storytellers themselves would have us believe, then we moderns ought to tread lightly so that what remains of Lanka's fabulous heritage is not roughly trampled underfoot in the headlong dash to 'advance' in the direction of self-interest and material comfort.

Equally disturbing is the prospect that modern society, already shaken to its foundations by its own uncontrollable excesses, may before long have to find urgent ways and means to adapt itself to a social and environmental cataclysm of its own making. Wisdom, preserved and transmitted in any fashion whatsoever, may already be the world's most valuable commodity.

Perhaps, then, it is also time for educated Sri Lankans to consider just what it is that villagers have with unswerving conviction preserved for centuries. Whatever it is, it has repeatedly played a critical role in helping Lanka's human culture to regenerate itself while retaining its age-old identity in the face of unprecedented challenges.

Hence, rather than to look abroad for solutions to new problems, Sri Lankans might do well to look beneath their feet for wealth and resources that had been lying unvalued, unnoticed and unused even in broad daylight for all these centuries. And the rest of the world would be well advised to do likewise.

This article by Patrick Harrigan first appeared in The Sunday Times (Colombo) of 26 November 1989.

|