|

|

||||||||||||

Lanka's Cosmography Down the Agesby Patrick Harriganfrom Sri Lanka and the Silk Road of the Sea edited by Dr. Senake Bandaranayake and jointly published by UNESCO and the Central Cultural Fund (Colombo: 1990)

Across the ancient world from Europe to the Far East and from remote prehistory, down to modern times, the island known variously as Lanka, Serendib, or Taprobane has powerfully influenced the imagination of travelers, storytellers and students of sacred geography, or cosmography, the mapping of the known universe. Down the centuries, a host of colorful characters, from Gautama Buddha to Sinbad the Sailor, has in fact or in legend visited this resplendent isle to partake of its reputation for wisdom, wealth, and enchantment. Only recently have modern scholars, through computer training, networking, and of course, use of the internet, begun to analyze in depth the patterns of structure and meaning common to all ancient accounts of Lanka, as truly fabulous as most of them are. In this article, a modern investigator of traditional lore surveys the field of Lankan cosmography down the ages with special attention to the methodology and purpose of 'sacred geography'. Patrick Harrigan, M.A. (University of Michigan), studied sacred geography from the late German Swami Gauribala. He now serves as acting editor of the Kataragama Research and Publications Project. In the beginning, say certain Sri Lankan oral and poetic traditions, the First Man descended from the Sun and alighted upon Sri Pada—Adam's Peak. The Old Man climbed down from upon the sacred Mountain and a great multitude of descendants followed in his footsteps. Once and for all, he set an example for others by following the well-beaten jungle path laid down by the wide and gentle giants of the forest, the great elephants. This path took him southwards along the banks of the Walawe Ganga and then east to the banks of the Menik Ganga. Here, where the great gajas or elephants rested, he planted his spear under a tree and stayed. This Gajaragama, 'the home of the elephants', is known to us today as Kataragama. Alive and well to this day, the solar hero's undying spirit still survives in Kataragama, where even now his mysteries are openly celebrated. There they preside in subtle majesty: the inscrutable elephant-god Ganapati ('Lord of the Herd') together with his 'younger brother' Skanda Kumara, the tender prince and chief who is the Swami or Lord of Deviyange Kaele, 'the God's own Jungle'. Together the two, related as Elephant and Lion, form the gaja-singha, traditional emblem of sacerdotal authority and temporal power.

This is but one of many poetic accounts of the cosmography or traditional 'sacred geography' of Sri Lanka that, considered together, paint a genuinely fabulous picture of Lanka's position in the ancient world. And this glowing picture of the island was not a mere conceit of its inhabitants only, for some of the most incredibly insightful accounts of the island come from the traders, pilgrims, and adventurers from other corners of the earth who helped to make Lanka renowned throughout the world. Storybook KingdomIn fact, most of the cosmographical descriptions of Taprobane or Serendib, as the island has also been known, come to us in the form of oral or written accounts of the visits of diverse and colorful protagonists around whom a host of stories is woven. Thus, among other fabled characters said to have come to this island are such luminaries as Gautama Buddha, god Vishnu (in, His Ramavatara or Descent as God Rama), wargod Skanda-Murugan (who decided to stay), Alexander the Great in his fabled quest to see the far end of the earth), al-Khidr ('the Green Man', mysterious teacher of Moses from quranic lore), and travelling merchant-adventurers like Sinbad the Sailor and Marco Polo. More important than issues of the historicity of these visits is the undeniable existence of the stories themselves, for all describe a marvelous isle in terms that reflect a more or less deep awareness of Lanka's sacred geographical character and position. Taken together, they suggest the existence of an arcane traditional science, known virtually worldwide to a handful of specialists, that recognized Lanka as one of its practical paradigms. Most indicators or clues remain part of living oral traditions, while others have found their way into such literary works as the Ramayana and the Mahavamsa. These various cosmographical accounts all agree in describing Lanka as a kind of storybook kingdom, a magical isle of legendary proportions where the topsy-turvy and miraculous are commonplace. At the root of this is a non-temporal but spatially-oriented worldview that makes no fundamental distinction between the sensible world of empirical extension and the cognizable worlds of mythic reality where all occurs in principio, i.e. 'at the source' rather than at some chronological 'Beginning'.

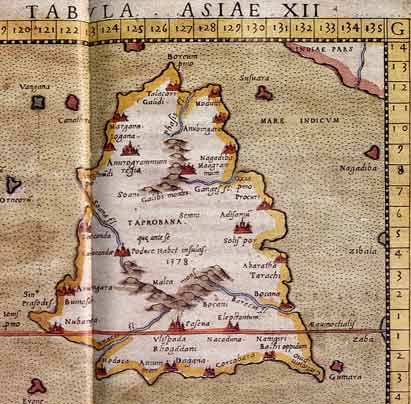

This cosmological principle or source, not surprisingly, lends itself easily and naturally to cosmographical expression in such familiar spatial distinctions as higher-lower, before-behind, and North-South, etc. In this sense, every point is reckoned to have its own character or sacred qualities, its own 'story' that maps its relation to other points. Traditional cosmography, therefore, represents more than the plotting of distances between points. Rather, it is the greater story of these points, of how they differ from each other, and of how they are all tied together. Properly speaking, cosmography or sacred geography is the 'lay of the land' in the sense of the songs sung and tales told about it. Small wonder, then, that spatially oriented thought was cultivated to such a remarkable extent here in Asia over the course of ages. The result is a wealth of arcane lore expressed in terms of cosmography, astrology, grammar, and iti-hasa or epic storytelling. Even the Mahavamsa derives from this tradition and is no exception. Topsy-TurvySacred geography or cosmography, the mapping of the ordered universe, is one such vidya or sacred science for which Lanka has long been famous. As the Roman historian Pliny notes in the sixth book of his 37-volume Natural History written in the first century AD, the people of the ancient Mediterranean world considered Taprobane or Lanka as another world altogether, such that many took it to be the place of the Antipodes ('where feet are reversed'), calling it the Antichthones world, where everything is inverted, upside-down or topsy-turvy. Ptolemy of AlexandriaA century later, Ptolemy of Alexandria, the 'Father of Modern Geography', was able to compile a picture of Taprobane of such accuracy that it remained in use for over sixteen hundred years. Living as he was in Alexandria at the time of its ascendancy as a world center of traditional sciences, Ptolemy's work might reasonably be expected to reflect an intimate familiarity with then-current mystery traditions, even where distant Taprobane is concerned. This spatially-oriented mythical or magical thinking is clearly to be distinguished from the conventional rationality of modern historicism or the ruthless logic of the marketplace. In most of South Asia to this day, historicism is still a modern import with scarcely any impact on grassroots, day-to-day thinking of people whose values drive from age-old traditions. Indeed, Ptolemy's map of Taprobane is strewn with clues implying that the island is, in fact, the place of the Antipodes, a kind of hypothetical 'East Pole' or far end of the earth, literally 'where feet are opposite'. And not only does Ptolemy reckon Taprobane to be many times larger than the island we know today, but he also assumed that it lies upon the earth's equator, for this is what ancient mariners firmly believed: that the Antipodes region lies upon the equator where day and night and seasons are all equal. Equally important to this picture of Taprobane as the topsy-turvy Antichthones world is Ptolemy's recognition of the existence of a Dionysi seu Bacchi Oppidum (Latin: 'town of Dionysus or Bacchus') in the close vicinity of Kataragama (see Ptolemy's map). Bacchus or Dionysus, the ancient Greek and Asian god of theatre, netherworld intrigue and ecstatic torchlit processions, also bears extraordinary structural similarities to god Kataragama that are outside the purview of this study but which Ptolemy and others must have clearly recognized. How much more Ptolemy and his informants knew but would not write on his map of Taprobane must remain a tempting subject for speculation. Lanka DeepaWhen we turn to the island's own sacred geographical traditions, an enormous wealth of lore confronts us. There are legends and beliefs peculiar to the island's Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, and Christian communities, as well as indigenous traditions preceding the influence of major religions. All participate to some extent in this underlying mystique of the island's reputation for the fabulous, as witnessed by the persistent vitality of cults centering upon certain shrines still widely believed to emanate subtle influences that may be propitiated in diverse fashions. Indeed, the very word 'serendipity' was coined to express this propensity of Lanka or Serendib for happy surprise discoveries of marvelous things.

This belief in the congruence of name and form (Sanskrit: nama-rupa) is further illustrated in the traditional etymology of the island's ancient name Lanka, which is interpreted to mean 'a shining point'. The island's modern honorific prefix Sri similarly denotes radiance, hence its distinction as 'the resplendent isle'. Not ,coincidentally, Lanka is also widely believed to be Dhamma Deepa, a Pali rendering of either of two Sanskrit terms, Dharma Dweepa 'the island of Dharma' or Dharma Deepa 'the lamp of Dharma', Similarly, the term Lanka Deepa is regarded as a shining point in a sea of dark water. This ancient philological relic persists in popular usage as an intriguing survival (if ancient poetic cosmography. Likewise, all of Lanka was known as Naga Deepa, literally 'Dragon's Lamp' or 'Isle of the Naga People' depending upon the context. Axis MundiAll of these terms associate the island Lanka with concepts of luminosity and fairness or justice (Dharma), motif which appears over and over in the most diverse surviving accounts, regardless of the agency or 'source' of the accounts. Typically, accounts of the island portray it as fulfilling the role of a half-real, half-imaginary or hypothetical Antipode or 'East Pole' that is simultaneously the far end of the earth and the center or hub around which the world is said to turn in a metaphorical sense. Hence, Lanka has long been identified with the axis mundi or ‘World Axis' that is also the stambha or fulcrum of the universe. Literally meaning a prop, support, or pillar, the stambha is described as being a shaft of light piercing the upper, lower, and intermediate regions (tri-loka, ‘the three worlds') and ordering the activity or cyclical turning of the universe (Latin uni-versus ‘all in one turn', hence 'complete'). For this reason, the stambha is also associated with the Supreme Being and traditional concepts of kingship. All these are recurrent elements in the traditional cosmography of Lanka. Axis and WheelNo doubt, the island's reputation as the principal source of such royal trappings as rare jewels, spices, elephants and peacocks has influenced this association of Lanka with concepts of kingship, and is also a point worth considering. The ideal monarch, furthermore, was long reckoned to be the living analog of the axis mundi, symbolized by the vertical shaft of the royal scepter (Tamil: cenkol) that he (or she) alone is authorized to wield. Accordingly, the vertical or polar shaft, along with the Dharmacakra or 'Wheel of Justice' through whose empty hub the unmoving shaft passes, are both ancient emblems of just kingship. Closely associated with the symbolism of the world axis and wheel is the notion of the cakravartin or 'Wheel Turner', the Universal Monarch or world conqueror, well-represented in the figure of Alexander the Great and whose weapon of choice, it is said, was the lance. All of these royal or divine attributes—luminosity, power, firmness, wisdom, justice, kingship and so on—converge, as it were, in the fundamental imagery that has for millennia been employed not only to name the island but also to describe its svabhava or natural disposition. This structural convergence of names and attributes coalescing upon a common source or origin is itself an analogue to the solar Dharmacakra image with its multiple converging spokes or rays. The empty hub, saddle, or throne at the center is understood to be the seat of the Person in the Sun whose mysterious life-supporting power acts through the stambha or axial shaft upon all living things under the sun. Storytelling MatrixIn its capacity as a focus or fulcrum for the human imagination right down the ages, Lanka has served faithfully as a kind of matrix for the generation of allegorical tales of wisdom transmitted in the guise of odysseys of mystery and adventure. Over and over, these recurrent themes of disguised majesty, magical kingdoms, and hidden treasure have re-surfaced in fresh versions that reveal the depth of awe and mystery our ancestors felt towards this enchanted isle of Serendib or Lanka. Firmly convinced that this Lanka is not in any sense a flat two-dimensional entity, their accounts are tiered or layered into a surface story for all to enjoy and, simultaneously, progressively deeper allegorical levels that lead the listener closer to the storyteller's own understanding. The resulting descriptions disclose a rich texture and depth that can scarcely be duplicated. Each in their own way, these early explorers discovered in Lanka a cosmographical hierarchy that could only be faithfully portrayed by analogy, by verbally mirroring the entire cosmos as it was seen reflected on earth. LemuriaThe cosmography of Lanka, then is the story of a 'shining point' in the midst of an ocean at the very end or center of this world of ours. It is a shining lamp or island, Lanka Deepa, situated somewhere, sometimes visible and sometimes hidden, such that it is also the fantastic Serendib or Lemuria, the part-real part-imaginary ‘East Pole' or Antipode so far removed from our humdrum modern perspective. The hub of the world, it is all this and the site of the mysterious vertical shaft or axis mundi as well. Despite its deceptive appearance of inactivity, it is the seat of mysterious divine power. This cosmographer's Lanka, then, may be seen as an island or lamp of consciousness that is firmly fixed, a pole star of sorts that is also a point of reference called the center of the world. Situated where heaven and earth converge, this point is explained in Lankan oral tradition as being nowhere unless in one's own heart, the living lamp of awareness that is the seat of one's unseen guide through life. It is firmly fixed at the center of the world, here and now, between a non-existent past and an unrealized future. And yet, despite this self-confession, traditional cosmographies nevertheless postulated that an enchanted isle of Lanka or Lemuria does indeed exist somewhere above or: below the surface of the earth. Each, according to his or her own fashion, set out to explore the reputed magical kingdom and reaped experiences that chart the land of their dreams. These paradigms or patterns survive in the form of fables and fabulous adventures that literally come from the Heart. They are the stuff that cosmography or sacred geography is made of, the flights of imagination that map the contours of two worlds, interior and exterior, that are seen to reflect and even shape one another. East PoleThe original Lanka, according to oriental cosmographers, was far greater than the Lanka on today's world map. Also called Lemuria in some accounts, it was a continent-sized island kingdom of fabulous wealth, technology and magical sciences. Its capital Lankapuri was situated in the heart of the kingdom at 0° latitude, 0° longitude, i.e. at the center of the world on the equator. So important was the location of Lanka's capital to ancient cosmographers that they took it as 0° longitude as the 'Meridian of Lanka', just as we moderns reckon longitude arbitrarily in relation to Greenwich Observatory near London. In other worlds, geographically speaking, Lanka or Lankapuri at 0 degrees latitude 0 degrees longitude was the center of the world for the ancients, and the Meridian of Lanka—-said to pass through the royal observatory of Ujjaini or modern Jaipur—-was the reference meridian used by ancient cosmographers and astrologers. Even in Ptolemy's time and much later also, the conviction persisted that Lanka or Taprobane is much greater than our senses might lead us to believe. Could the ancients have known something that we moderns have forgotten? Fortunately, it has not been forgotten entirely. No doubt, our modern civilization would do well to heed the example of Lemuria or Lanka. RavanaPerhaps the best-known legendary Lanka, however, is that of the Ramayana, the epic story of the great solar god Vishnu's descent as Lord Rama to restore order to the world following the havoc and mischief raised in remote antiquity by Ravana, the King of Lanka in those days. So much power centered upon Ravana and Lanka that the gods themselves became incapacitated and had to turn to the high God to beg Him to incorporate Himself on earth and set things straight. The resulting Great War, like that of the Mahabharata, remains etched in human memory even today. Not surprisingly, local legends of Lanka display a great deal of sympathy for this legendary bhumiputra or 'son of the soil' who rose to an extraordinary height before his downfall at the hands of none less than the great God Himself. In fact, far more local legends celebrate places and incidents in the career of Ravana than of Rama, who is meek and colorless in contrast to the robust and more human-like King Ravana. Interestingly, the same oral tradition tells the story of a Patala ('sunken') Lanka where the surface Ravana's powerful elder brother Mayil Ravana ('Peacock Ravana') rests peacefully until entreated by his younger brother to join the fracas on the surface of Lanka. Island SpiritsLong after Raven's time, Lanka was still considered to be a mysterious haunt not for humans but for terrific demons (rakshasas), mischievous spirits (yakshas) and serpent-totemists (nagas). Even the early Lankans themselves were reckoned by visitors and immigrants alike to partly human in appearance only to mask better their alien character. Whatever the truth of the matter, the wild spirits of Lanka were never entirely driven out as many would have preferred. Instead, oral tradition records, they were driven underground into caves and shadowy jungle retreats where they still brood to this day, ready to change forms on a moment's notice whenever opportunities for mischief arise. Even today, the vitality of spirit cults associated with particular shrines bears mute testimony to the survival of mysterious living forces whose geographical fixedness in Lanka is their most persistent trait. Over the centuries, a complex network of shrines dedicated successively or simultaneously to shamanistic, Brahminical, Buddhistic, Christian or Islamic principles or powers has survived the transition over centuries to remain as the silent bedrock for almost every faith under the sun. It is this network, matrix or foundation that ancient cosmographers sought to map and describe. If their quixotic labors have more often than not been misunderstood, it is largely because of the profundity and depth of their arcane knowledge and because of the consequent difficulty of communicating its scope and principles through anything but parables, fables and metaphors.

Sinbad the SailorSome splendid applications of these cosmographic principles are found in the great compendium of traditional Arabic storytelling, the Alf Laylah Wa Laylah or 'Thousand and One Nights'. In it, the unanimity (Sanskrit: mahasammata) of traditional thought clearly expresses itself for those who hold the metaphorical key to the Kingdom, while those who do not are both entertained, and elevated merely by hearing and appreciating. Because of the simplicity, beauty and elegance of its treatment of Lanka or Serendib and because of its usual dismissal at the hands of 'serious' modern people, it is worthwhile here to have a second look at the case of Sinbad the Sailor. Sinbad, the narrator and protagonist of his own strange and wonderful adventures, is reputed to have been a highly-successful merchant-seafarer during the caliphate of Harun er-Rashid. A native of Baghdad, he once agreed to narrate the story of his life 'so that all might know his strange adventures and conjecture no longer as to the source of his marvelous wealth' (my italics). Sinbad proceeds to relate the story of his Seven Marvelous Voyages of profit and adventure of which, he tells us, each one was more marvelous than the one before it. The first five journeys are truly bizarre storybook adventures in mythical lands and oceans teeming with wonders. But his most wonderful journey of all, Sinbad claims, were those to Serendib, the sixth and seventh voyages. And yet these greatest of marvels, unlike his earlier escapades, together form an entirely plausible scenario of two successive visits to Serendib from Baghdad. For the high point of all the adventures of Sinbad the Sailor was his service and friendship to the King of Serendib, 'whose name and power and learning are known through all the earth', Serendib, Sinbad the Sailor informs us, is a kingdom of unrivalled splendor and magnificence. There the day and night are equally divided the whole year round and, when the sun rises, its light bursts suddenly upon the earth. There the fragrance of spices fills the air and rare jewels glitter in the streams of a lofty mountain (i.e. Adam's Peak). But when Sinbad and his seafaring companions first land in Serendib, they find 'themselves shipwrecked and hemmed in by impassable mountains. One by one his shipmates die of tropical fever until Sinbad alone remains literally to dig his own grave and wait for the end to come. But Sinbad's kismat or destiny is otherwise. Driven to the brink of madness, he relates how at that very point he discovers a river that he had not seen before, one that comes gushing forth from out of one mountain and into another. With little to lose but his own life, Sinbad builds a raft for himself and his precious goods. Lashed to the raft, he boldly enters the torrent and is hurtled wildly into the dark mountain depths until he passes out from sheer terror. When Sinbad awakes, he finds himself still lying upon the raft. But the sun is shining upon him, tropical birds are singing, and there are trees on all sides. He is floating upon a lake and dark-skinned, long-haired inhabitants are gathering on the shore. They speak in a language strange to Sinbad, but one of them steps forward and welcomes him in his native Arabic. He is soon plied with island hospitality and asked to relate his story. Filled with wonder at Sinbad's adventures, they urge him to meet the King of Serendib and relate such wonders to His Majesty. Sinbad does encounter the world-renowned monarch, and from his grace and magnificence he knows that he is in the presence of the King of Serendib himself. Marveling at Sinbad's story, the King addressed him in Arabic, saying "Thou art greatly favored by destiny; wherefore I join my happiness with thine at thy deliverance and safety". Sinbad further relates that: "The delights of this realm herd me enthralled for a long time, so that I forgot my own country... But, on a day when I ascended the high mountain and looked far out across the sea, I seemed to hear the voice of my own land calling to me. Then, with that far call still in my ears, I went to the King and asked him to let me go. At first he demurred...but when I pressed for his permission, he relented and gave me a large sum of money for my journey, and also many gifts." (my italics) The King's gifts to Sinbad are fabulous indeed, but most fabulous of all, we are told, is the gift of a jeweled goblet or grail that Sinbad is to deliver to the Caliph of Baghdad together with a message of friendship and goodwill. He returns home to a warm welcome from the Caliph Harun-er-Rashid, who is himself the protagonist of many stories of wisdom and who later dispatches Sinbad back to see the King of Serendib for his seventh and ultimate voyage. Apart from revealing an actual familiarity with the geographical Lanka or Serendib, the story of Sinbad the Sailor also betrays an intimate knowledge on the storyteller's part of the principles applicable to Lankan cosmography down the ages. Particularly, the metaphorical dimensions of Sinbad's meeting and befriending the legendary King of Serendib to become his messenger and ambassador to the Caliph of Baghdad and all the Arab world deserve deep reflection. Like another gem of Middle Eastern lore, 'Attar's poem 'The Conference of the Birds', the marvelous journey to meet the King of Paradise, is also an allegory mapping the yearning soul's journey to meet its Lord. Sinbad the Sailor's fabulous story is of special interest to students of cosmography, for within it he confides to listeners a description not only of what (or who) is to be found in this enchanted Serendib, but more importantly how to arrive there and find it, i.e. 'the source of his marvelous wealth'. He tells, for example, how he had to survive many adventures only to reach the point of despair and certain death before plunging into the magical living waters that would whirl him deep beneath the surface to emerge into an entirely different world of staggering wealth and felicity. In this fashion, Sinbad's account of Serendib is fully in agreement with the principles employed down the ages by ancient cosmographers to paint an in-depth picture of Lanka. Simultaneously, they sought to describe both the inner and outer journeys of adventure and discovery for which this island is so famous the world over. The same 'shining point' at the center of the outer geographical world was clearly seen to be a functional analogue, and therefore a magical gateway of sorts, to the much greater Lanka hidden within the human heart. That Lanka, still very much alive and reachable, is the real source of marvelous wealth, mystery and majesty. From Sri Lanka and the Silk Road of the Sea, edited by Dr. Senake Bandaranayake and published by UNESCO and the Central Cultural Fund, Colombo (1990) Patrick Harrigan (M.A., University of Michigan) studied sacred geography and allied subjects under the tutorship of German Swami Gauribala from 1971 until German Swami's samadhi in 1984. In 1972 he walked Pada Yatra from Jaffna to Kataragama with German Swami and since 1988 he has walked annually from Trincomalee as the Kataragama Devotees Trust's Pada Yatra field representative. Since 1989 he has been acting editor of the Kataragama Research Publications Project. Kailasa to Kataragama: Sacred Geography in the cult of Skanda-Murukan Dionysus and Kataragama: Parallel Mystery Cults SacredSites.com Sacred Site Pilgrimage Sacred sites of Lanka map

|