|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The Worship of Muruka or Skanda (The Kataragama God)by Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam (1853-1924)First published in the Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XXIX, No. 77, 1924.

This classic account of Kataragama may also be downloaded as a PDF (Adobe Acrobat) file for instant viewing and sharing.I.There is on the South-east coast of Ceylon a lonely hamlet known as Kataragama[1] in the heart of a forest haunted by bears, elephants and leopards and more deadly malaria. The Ceylon Government thinks of Kataragama especially twice a year, when arrangements have to be made for pilgrims and precautions taken against epidemics. Hardly anyone goes there except in connection with the pilgrimage. General Brownrigg, Governor and Commander-in-Chief, visited this desolate spot in 1819 at the close of military operations in the Uva country, and seven decades later Sir Arthur Gordon (afterwards Lord Stanmore) who attended the festival in July, 1889. Sportsmen are drawn to this region by the fame of its sport, but Kataragama itself is outside the pale of their curiosity. Few even of our educated classes know its venerable history and association. It was already held in high esteem in the third century before Christ, and is one of the sixteen places said to have been sanctified by Gautama Buddha sitting in each in meditation.[2] The Mahavamsa (XIX. 54), in enumerating those who welcomed the arrival at Anuradhapura of the Sacred Bodhi-tree from Buddha-Gaya in charge of Sanghamitta, the saintly daughter of the Indian Emperor Asoka, gives the first place alter the King of Ceylon to the nobles of Kajara-gama, as Kataragama was then called. It was privileged to receive a sapling (ibid, 62) of which an alleged descendant still stands in the temple court. About a third of a mile off is the Buddhist shrine of Kiri Vihāre, said to have been founded by King Mahānāga of Mahagama, cir. 300 BC.

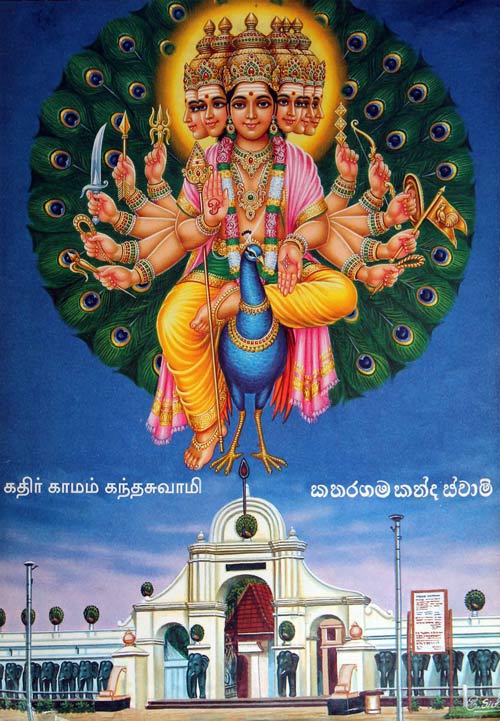

Kataragama is sacred to the God Kārttikeya, from whom it was called Kārttikeya Grāma (“City of Kārttikeya”) shortened to Kajara-gama and then to Kataragama. The Tamils, who are the chief worshippers at the shrine, have given the name a Tamil form, Kathirkāmam, a city of divine glory and love, as if from kathir, glory of light, and kāmam, love (Skt. kāma), or town or district (from Skt. graama). By Sinhalese and Tamils alike the God Kārttikeya is called Kandaswāmi; by the Sinhalese, also Kanda Kumāra (Kanda being the Tamil form of Sanskrit Skanda and Kumāra meaning youth), and by the Tamils Kumāra Swāmi, “the youthful god”. More often the Tamils call him by the pure Tamil name Murukan, “the tender child”. He is represented in legend, statuary and painting as a beautiful child or youth. The priests worship him with elaborate rites and ceremonies, the rustic with meal and blood offerings, the aboriginal Vedda invokes him also with dances in the primitive manner of the woods. The philosopher meditates on him in silence, adoring him as the Supreme God, Subrahmanya—the all pervading spirit of the universe, the Essence from which all things are evolved, by which they are sustained and into which they are involved—who in gracious pity for humanity takes form sometimes as the youthful God of Wisdom, God also of war when wicked Titans (Asuras) have to be destroyed, sometimes as the holy child Muruka, type of perennial tender beauty, always and everywhere at the service of his devotees. “In the face of fear,” says an ancient and popular verse,[3] His face of comfort shows. In the fierce battlefield, with ‘Fear not’, His lance shows. Think of Him once, twice He shows, to those who chant Muruka.” “A refreshing coolness is in my heart as it thinketh on Thee, peerless Muruka. My mouth quivers praising Thee, lovingly hastening Muruka, and with tears calling on Thee, Giver of gracious help-hand, Oh warrior! With Tirumurukarruppadai Thou comest, Thy Lady in Thy wake.”[4] The scene of his birth is laid in the Himalayas. His birth and exploits are described with poetic embellishments in the Skanda Purana, an epic poem which in its present Sanskrit form dates from about the fifth century and in its Tamil version from the eighth.[5] “Dearest,” cries a Tamil poet of the 1st century, “whom the cool blue waters of the tarn on great Himalaya’s crest received from the beauteous hands of the peerless one of the five (elements, i.e., Agni, god of fire) and who in six forms by six (Naiads) nourished became one.” Though born on those distant northern mountains, his home now and for over twenty centuries has been in the South, and his worship prevails chiefly among the Tamils. He appears to have been the primitive God of the Tamils and to have passed with them to the South from their supposed early settlements in North India. He is now little known or esteemed in the North, where he has given way to other gods, as the Vedic gods Indra, Varuna, Agni gave way to Siva, Vishnu, etc., and as in Greece, Uranus gave way to Kronos and he to Zeus.[6] Skanda had a great vogue in the north for centuries among the Aryan, Scythian, Mongolian, Hun and other invaders who succeeded the Dravidians, and, intermingling with them, became the ancestors of the present inhabitants. In an Upanishad of about the ninth century BC. he is described as giving spiritual instruction to the rishi Narada and is identified with the great sage Sanatkumara (Chandogya Upanishad, VII. 262).[7] The image of the God Skanda appears in the coin of King Huvishka who in the beginning of the second century of the Christian era ruled over an empire extending from the Central Himalayas and the river Yamuna to Bactria and the river Oxus.[8] In the third century, the great Sanskrit poet Kalidasa wrote his classic poem on the god’s birth (Kumara Sambhava, “Birth of Kumara”). In the Meghaduta (Cloud-Messenger) of the same poet, the hero, an exile from home, in sending a message to his sorrowing wife, bids the cloud halt at the god’s shrine on Mount Devagiri (near Ujjain). “There change thy form and showery roses shed In an interesting Sanskrit drama of the first century (attributed to King Shudraka and known as the Mrichchakattika, “The Little Clay Cart”, in which the scene is laid in Ujjain [Editor’s note: Mrichchakattika has since been attributed to Kalidasa]) the god is invoked by a Brahmin burglar as the patron of his tribe,[9] for he is the god of war and they are soldiers of fortune waging war against society by operations akin to mining and sapping in war. At the present day, in Bengal, he is worshipped one day in the year during the Durga puja festival, and especially by those desiring offspring. But wherever Tamil influence prevails, he is held in preeminent honour and dignity. The Tamils regard him as the guardian of their race, language and literature and are bound to him by special ties. He is reputed to have arrived in Lanka (Ceylon) in a remote age when it was a vast continent—the Lemuria, perhaps, of the zoologists, stretching from Madagascar to near Australia—and was ruled by a Titan, the terror of the celestials. In answer to their prayers, the god was incarnated as the son of the Supreme God Mahādeva or Siva. He led their hosts to Lanka and destroyed the Titan after mighty battles, his lance seeking the foe out in his hiding in the ocean.[10] The Titan was then granted forgiveness for his sins and was changed into a cock and a peacock, the former becoming the god’s banner and the latter his charger.[11] These events, with their moral significance of the expiation of sin, are yearly celebrated by festivals and fasts in Tamil lands in the month of Aippasi (October-November) ending on the 6th day of the waxing moon (Skanda Shashti). On such occasions, the Tamil Kandapuranam is read and expounded with solemnity, also at times in private houses, such reading being deemed efficacious, apart from spiritual benefits, in warding off or alleviating disease and danger and bringing good fortune.

The lance, the instrument of chastisement and salvation, is understood to typify his energy of wisdom (j&ntiledāna sakti, somewhat corresponding to the Christian sophia) and is often the only symbol by which he is worshipped in the temples. In others, he is represented with six faces, or aspects of his activities, and riding a peacock with his consorts, Teyvayānai (Skt. Devasenā) and Vall who are regarded as his energies of action and desire respectively (kriya sakti and ichcha sakti). The former was daughter of Indra, King of the celestials, and Valli was a Vedda princess whom, according to Ceylon tradition, he wooed and won at Kataragama. She shares in the worship of millions from Kashmir and Nepal to Dondra Head, and the priests (kapuralas) of Kataragama proudly claim kinship with her. He deigned, according to theologians, to set the world a pattern of married life, for the due discharge of its duties leads to God no less surely than a life of renunciation. In the Tamil epic the poet introduces a courting scene in which occurs this appeal: “Highland maid of Kurava clan, could that I were the pool in which thou bathest, the perfumed unguents thou usest, the flowers thou wearest.” It recalls Anakreon’s lover[12] “I would be a mirror, that Some of the stories of his birth and childhood seem to have traveled far west and left traces in the religion and literature of ancient Greece. He is said to have issued from the frontal eye of Siva as six sparks of fire. They were received by Agni, God of fire, and cast into the Ganges, from which they passed into the Himalayan lake Saravana and there were transformed into six babes. These were suckled by the six nymphs of the constellation Pleiades (Krittika) and became one on being fondly clasped by the Goddess Uma. He has many names: the Tamil Pingala Nigantu gives 37. Some of them are derived from the incidents I have mentioned: Agni-bhu, fire-born, from the manner of his birth; Gangaja or Gangesa from the association with the Ganges, (Tam. Kankesan, which gives the name to one of our northern ports, Kankesanturai, where his sacred image is said to have been landed in the 9th century)[13]; Saravana Bhava, born in Saravana, a Himalayan Lake (Tam. Saravanamuttu, pearl of Saravana); Karttikeya from his foster-mothers Krittikās (the Pleiades); Skanda, the united one, because the six babes became united into one.[14] The more probable derivation [Editor’s note: the scientific etymology] is from the root skand, to leap. Skanda would then mean the Leaper of his foes. He is also called Shanmukha (Tam. Sanmukam or Arumukam) as being six faced. Being the one and only Reality, he is called in Tamil Kandazhi, which is explained as “reality transcending all categories, without attachment, without form, standing alone as the Self.”[15] It is as such that he is adored at Kataragama, no image, form or symbol being used (see infra). Kataragama thus holds a unique place among his numerous places of worship in India and Ceylon. The worship of Skanda has suffered no decline in Ceylon from the

introduction of Buddhism 24 centuries ago. The “Kataragam god” (Kataragama

Deviyo) has a shrine in every Buddhist place of worship, and plays a prominent

part in its ceremonials and processions. In the great annual perahera of Kandy,

he had always a leading place; Buddha’s Tooth, now the chief feature of the

procession, formed no part of it till the middle of the 18th century, when it

was introduced by order of King Kirti Sri Rajasingha to humour the Buddhist

monks he had imported from Siam. The town of Kalutara on the southern bank of

the Kalu Ganga appears to have been specially associated with the god and still

retains the name Velapura, “the City of the Lancer”, the lance being his favourite

weapon. The opposite bank of the town is called Desestra Kalutara, i.e.,

Deva Satru or the enemies of the gods. These names are perhaps relics of an

unsuccessful movement to limit his jurisdiction to the southern half of the

Island, the defeated opponents being pilloried by his votaries as demons. His

shrines, however, are now as common north as south of the river: both among

Buddhists and Hindus he is the god par excellence. King Dutugemunu in the first century BC, according to ancient tradition, rebuilt and richly endowed the temple at Kataragama as a thank-offering for the favour of the god, which enabled him to march from this district against the Tamil King, Elāla, and, after killing him in battle, recover the ancestral throne of Anuradhapura. Dutugemunu’s great-great-grandfather Mahanaga, younger brother of Devanampiya Tissa, had taken refuge in the Southern Province and founded a dynasty there, and Anuradhapura was for 78 years (with a short break) ruled by Tamil Kings, of whom Elala (205-161 BC) was the greatest. Dutugemunu conceived the idea of liberating the country from Elāla. While his thoughts were intent on this design day and night, he was warned in a dream not to embark on the enterprise against his father’s positive injunctions, unless he first secured the aid of the Kataragama god. He therefore made pilgrimage thither and underwent severe penances on the banks of the river, imploring divine intervention. While thus engaged in prayer and meditation, an ascetic suddenly appeared before him, inspiring such awe that the prince fainted. On recovering consciousness, he saw before him the great god of war who presented him with weapons and assured him of victory. The prince made a vow that he would rebuild and endow the temple on his return, and started on his expedition, which ended in the defeat and death of Elāla and the recovery of the throne. The incidents associating the Kataragama god with Dutugemunu’s victory naturally find no place in the Buddhist chronicle, the Mahavamsa, which glorifies him as a zealous champion of Buddhism.[16] The tradition is confirmed by a Sinhalese poem called Kanda Upata “Birth of Kanda”, for a MS. copy of which I am indebted to Mudaliyar A. Mendis Gunasekara. Stanzas 41 and 46 show that King Dutugemunu invoked the aid of the god, and received his help and built and endowed the temple at Kataragama in fulfillment of his vow. The royal endowment was continued and enlarged by his successors and by the offerings of generations of the people and princes of Ceylon. This old and once wealthy foundation has for years been in a woeful plight, from loss of the State patronage and supervision which it enjoyed under native rule and owing to the corruption and dishonesty of the Sinhalese trustees and priests in whom, under the Buddhist Temporalities Ordinance, its administration is vested. Its extensive estates have mostly passed into other hands, the property that remains is neglected, the temple buildings are in disrepair, and the daily services are precarious. The Hindu pilgrims, however, continue to flock in thousands, pouring their offerings without stint and wistfully looking forward to the day which will see the end of the scandalous administration. It is possible now to travel from Colombo comfortably by train to Matara and by motor to Hambantota and Tissamaharama. The last stage of about 11 miles beyond Tissamaharama is over a difficult forest-track and an unbridged river, the Menik Ganga, which in flood time has to be swum across there being no boats. In the thirties of last century, when good roads were scarce even in Colombo, my grandmother walked barefoot the whole way to Kataragama and back in fulfillment of a vow for the recovery from illness of her child, the future Sir Muttu Coomara Swamy. The hardships then endured are such as are yearly borne with cheerfulness by thousands traveling on foot along the jungle tracks of the Northern, Eastern and Uva provinces and from India. Nearly all are convinced of the god’s ever-present grace and protection and have spiritual experiences to tell or other notable boons, recoveries from illness, help under trials and dangers, warding off of calamities. I once asked an elderly woman who had journeyed alone through the forest for days and nights if she had no fear of wild elephants and bears. She said she saw many, but none molested her. “How could they? The Lord was at my side.” The verses cited on page 111 express the passionate feeling of many a pilgrim.

An old Brahmin hermit whom I knew well, Sri Kesopur Swami, was for about three quarters of a century a revered figure at Kataragama. He had come there as a boy from a monastery in Allahabad in North India in the twenties of last century. He attached himself to the Hindu foundation (next the principal shrine) of the Teyvanai Amman temple and monastery. This institution belongs to a section of the Dasanami order of monks founded by the great Sankaracharya of Sringeri Matham (Mysore). The lad after a time betook himself to the forest, where he lived alone for years, until he was sought out and restored to human society by a young monk, Surajpuri Swami by name, whom also I knew. The latter was a beautiful character, pious and learned, and with a splendid physique. He had been a cavalry officer of the Maharaja of Cashmere and, being resolved on a life of celibacy and poverty, found himself thwarted by his relatives who pressed him to marry and assume the duties of family life. Failing in their efforts, they brought the Maharaja’s influence to bear upon him, whereupon he fled from home and traveled as a mendicant until he reached the great southern shrine of Rameswaram, well known to tourists and a great resort of pilgrims. There (he told me) he received a divine call to proceed to Sri Pada, the “Holy Foot” (Adam’s Peak of English maps), which the Hindus revere as sacred to Siva and the Buddhists to the Buddha. Here he was ordered to proceed to Kataragama, where he would find a hermit in the forest whom he was to wait upon and feed with rice. This he did and brought the hermit to the temple. He soon gave up rice or other solid food and confined himself to a little milk; hence he was known as Pal Kudi Bawa. A very saintly and picturesque figure he was, revered for his childlike simplicity and purity, spiritual insight and devotion, and much sought after for his blessings. He died in Colombo in July 1898 at a ripe old age.[17] His remains were taken to Kataragama and a shrine was built over them by his votaries. His pupil Surajpuri survived him only a few months and died in November 1898. The old hermit told me of a saintly woman named Balasundari who lived there. She was the eldest child of a North Indian Raja, a boon from the Kataragam God in answer to a vow that, if blessed with children, the firstborn would be dedicated to his service. The vow was forgotten and a stern reminder led to her being brought by the father while still a child and left at Kataragama with a suitable retinue. She devoted herself to a spiritual life. The fame of her beauty reached the King of Kandy, who sent her offers of marriage, which she rejected. He would not be baulked and sent troops to fetch her to the palace. But, said the hermit, the God intervened and saved her. He brought the British troops to Kandy, and the King was taken prisoner and deported to Vellore in South India.[18] This was in 1814. The lady, thus saved from the king’s rough gallantry, lived to a good old age, loved and revered, and died at Kataragama after installing Mangalapuri Swami, who died in 1873 and was succeeded by my venerable friend Kesopuri.[19] In 1818 a rebellion broke out in the Kandyan provinces, excited by the chiefs smarting under the loss of rights and privileges guaranteed by the Kandyan Convention of 1815. The rebellion was suppressed with severity, especially in the Uva province, which (as Mr. White, C.C.S., states in his Manual of Uva, 1893) has scarcely recovered from the effects. It was towards the end of these military operations that General Brownrigg, the Governor and Commander-in-Chief, visited Kataragama. Dr. John Davy, F.R.S. (who was on the medical staff of the army from 1816 to 1820 and on the Governor’s staff during this tour) has in his “Account of Ceylon” (published 1821) described the tour in Uva and the visit to Kataragama. The Sinhalese Kapuralas were believed to be active participators in the rebellion. The custody of the principal temple was taken from them and delivered to the Hindu Monks, and a military guard was left to protect them. When the guard was removed some time later, the Kapuralas resumed forcible possession of the temple. The Hindu monks, whose abbot impressed Davy greatly, continued to be in charge of the Teyvayanai Amman temple and monastery. Speaking of the journey to Kataragama, Davy says (p. 403): “All the way we did not see a single inhabited house or any marks of very recent cultivation, nor did we meet a single native; dwellings here and there in ruins, paddy neglected, and a human skull that lay by the roadside under a tree to which the fatal rope was attached, gave us the history of what we saw in language that could not be mistaken.” Of Kataragama itself he says: “Kataragama has been a place of considerable celebrity on account of its Dewale which attracts pilgrims not only from every part of Ceylon, but even from remote parts of the continent of India, and is approached through a desert country by a track that seems to have been kept bare by the footsteps of its votaries.” The God, he says, is not loved but feared, and merit was made of the hazard and difficulty through a wilderness deserted by men and infested by wild beasts and fever. From the forlorn and ruinous condition of the place, Davy anticipated that in a few years the traveler would have difficulty in discovering even the site. The anticipation has not been realized, though over a century has now passed; the pilgrims are in fact more numerous and zealous than ever. Robert Knox, who in the seventeenth century spent 20 years of captivity in Ceylon, in his Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon published in 1861 in London, in speaking of the Eastern Coast, says: “It is as I have heard environed with hills on the landside and by sea not convenient for ships to ride; and very sickly, which they do impute to the power of a great god which dwelleth in a town near by they call Cotteragon, standing in the road, to whom all that go to fetch salt, both small and great, must give an offering. The name and power of this god striketh such terror into the Chingalayas that those who are otherwise enemies to the King and have served both Portuguez and Dutch against him, yet would never assist either to make invasion this way.” In the great Perahera at Kandy, in Knox’s time, there was no Buddha’s Tooth, but “Allout neur dio,[20] God and maker of Heaven and Earth, and Cotteragom Deyyo and Pottingt dio,[21] these three gods that ride here in company are accounted of all the others the greatest and chiefest.” Davy himself says (p. 228): “Of all the gods, the Kataragama God is the most feared…and such is the dread of this being that I was never able to induce a native artist to draw a figure of it.” This unwillingness was rather due to the fact that at Kataragama there is no figure of the god. He is not worshipped there in any image or form. A veil or curtain, never raised, separates the worshippers from the Holy of Holies, where, according to the best information, there is only a casket containing a Yantra or mystic diagram engraved on a golden tablet in which the divine power and grace are believed to reside. It is this casket which in the great festivals of July and November is carried in procession on the back of an elephant.[22]

The history of this tablet, according to a native tradition reported to me by Kesopuri Swami, is that a devotee from North India, Kalyanagiri by name, grieved by the god’s prolonged stay in Ceylon, came to Kataragama to entreat him to return to the North. Failing to obtain audience of the god, he performed for 12 years severe penances and austerities, in the course of which a little Vedda boy and girl attached themselves to him and served him unremittingly. On one occasion when, exhausted by his austerities and depressed by his disappointment, he fell asleep, the boy woke him. The disturbed sleeper cried out in anger, “How dare you disturb my rest when you know that this is the first time I have slept for years?” The boy muttered an excuse and ran pursued by him until an islet in the river was reached, when the boy transformed himself into the God Skanda. The awe-struck hermit then realised that his quondam attendants had been the God and his consort Valli. Prostrating himself before them and praying forgiveness, he begged the God to return to India. The Goddess in her turn made her appeal (Tamil: mankiliyappiccai) and begged that the god might not be parted from her. This the sage could not refuse. He abandoned the idea of the God’s or his own return and settled down at Kataragama where he engraved the mystic diagram (yantra) and enshrined it there for worship in buildings constructed or restored with the help of the ruling king of Ceylon. When in due course the sage quitted his earthly body, he is believed to have changed into a pearl image (muttu lingam) and, is still worshipped in an adjoining shrine under that name (Muttulingasvami). His pupil and successor was Jayasingiri Swami who received Governor Brownrigg at Kataragama and is admiringly described by Dr. Davy. He mentions as a special object of reverence the seat of “Kalana natha the first priest of the temple”, Kalana natha being Davy’s variation of Kalyana Natha alias Kalyana Giri. The seat is still very much as Davy described it: “The Kalana Madam is greatly respected and certainly is the chief curiosity at Kataragama; it is a large seat made of clay, raised on a platform with high sides and back, like an easy chair without legs; it is covered with leopards’ skins and contained several instruments used in the performance of the temple rites: and a large fire was burning by the side of it. The room, in the middle of which it is erected, is the abode of the resident brahmin. The Kalana Madima, the brahmin said, belonged to Kalana Natha, the first priest of the temple, who on account of great piety passed immediately to Heaven without experiencing death and left the seat as a sacred inheritance to his successors in the priestly office, who have used it instead of a dying bed and it is his fervent hope that like them he may have the happiness of occupying it at once and of breathing his last in it. He said this with an air of solemnity and enthusiasm that seemed to mark sincerity and, combined with his peculiar appearance, was not a little impressive. He was a tall spare figure of a man whom a painter would choose out of a thousand for such a vocation. His beard was long and white; hut his large dark eyes, which animated a thin regular visage, were still full of fire, and he stood erect and firm without any of the feebleness of old age.” The Ceylon King who helped the saint Kalyanagiri in the construction of the temples is, according to tradition, Balasinha Raja which, I take it, is equal to Bala Raja Sinha. The earliest kings of the name Rajasinha were Raja Sinha I (1581-1592) and Raja Sinha II (1634—1684), the patron of Robert Knox. There were four others of the name (with prefixes) from 1739 to 1815, when the dynasty came to an end. Considering the longevity of my friend Kesopuri Swami, who spent 70 years of his life at Kataragama and was probably 90 at his death, that Kalyanagiri was reputed to be a much greater yogi, as also his successor Jayasingeri, and that the practice of yoga is known to be favourable to health and long life, Kalyanagiri may be assigned to the time when Rajasinha II was administering the kingdom for his father Senerat, i.e., before 1634. The Government Agent of Uva, Mr. Baumgartner, in his report to Government on the pilgrimage of July 1897, mentions that Tilden R.M., who made an inventory of the temple property for the Provincial Committee, found nothing in the casket, the G.A.’s authority being the R.M.’s son, Taldena Kachcheri Mudaliyar, who had so heard from his father. It may be that the R.M. expected to find an image and did not notice the thin golden plate on which such diagrams are engraved, or the priests may have hidden it as too holy for a layman’s view. Davy speaks of the “idol being still in the jungle “ (p. 421) at the time of his visit in 1819, having been hidden away during those troublous times. II.The earliest account of the worship of Muruka is to be found in an ancient Tamil lyric, the delight of scholars and often on the lips of others, even if not fully understood. To appreciate its significance, religious, historical and literary, some idea of the early literature of the Tamils is necessary. Ancient Tamil history has for its chief landmarks three successive literary Academies established by the Pandyan Kings of South India, who were great patrons of literature and art. In this institution were gathered together (as the Acadèmie Française found by Cardinal Richelieu in 1635 and copied in other European countries) the leading literati of the time. The roll of members included royal authors of note and not a few women who were poets and philosophers. New works were submitted to the Academy for judgment and criticism, and before publication received the hallmark of its approval. The Academy was the jealous guardian of the standard literary perfection and showed little mercy to minters of base literary coinage. The first two Academies go back to an almost mythical period and their duration is counted by millenniums. The Tamils having a good conceit of themselves and a passionate love (equaled in modern times, I think, only by the French) of their mother tongue have assigned to it a divine origin and made their Supreme God Siva the president of the first Academy and his son Muruka or Skanda a member of the Academy and the tutelary god of the Tamil race. Both deities are represented as appearing on earth from time to time to solve literary problems that defied the Academy. The seats of the first and second Academies (old Madura and Kapadapuram) were the two first capitals of the Pandyan dynasty, and are said to have been submerged by the sea. The Pandyan kingdom was already ancient at the beginning of the Christian era. In the 4th century BC Megasthenes, ambassador of Seleucus at the court of King Chandragupta at Pataliputra, speaks of the country as ruled by a great queen called Pandaia. Then and for some centuries afterwards, the Pandyan country covered the greater part of the Madras Presidency, and included the native states of Mysore, Cochin and Travancore, and was bounded on the North by the sacred hill of Venkadam (Tiruppati, 100 miles northwest of Madras) and on all other sides by the sea. The southernmost point, Kumari (Cape Comorin of the English maps), is called after the “Virgin” Goddess Kumari, another name of Uma or Sivakami, consort of Siva, “Mother of millions of world-clusters, Her temple crowns the headland as it did in the time of the Greek geographer Ptolemy (140 AD) and earlier…In the “Periplus of the Erythrean Sea” (cir. 80 AD), a manual of Roman or rather Egyptian trade with India and a record of the author’s observations and experiences as merchant and supercargo, it is stated, “After this there is in the place called Komar, where there is (probably a fort or a temple) and a harbour where also people come to bathe and purify themselves…it is related that a goddess was once accustomed to bathe there.” The worship at the temple and the bathing in the sacred waters of the sea still continue. At the time of the first and second Academies, the land extended far south of Kumari, which was then the name not of a headland but of a river. South of it up to the sea were 49 districts whose names are given and which were intersected by a river called Pahruhi. All these are said to have been swallowed by the sea. There are poems extant written before the submersion as e.g., Purananuru 9, where the poet wishes his patron the Pandyan King Kudumi long life and years more numerous than the sands of the Pahruhi river. Traces have been discovered of a submerged forest on this coast. Was this part of the submerged Lemurian continent referred to at p. 113, or a later submersion? One or other of the submersions which destroyed the first and second Academies may have been identical with that recorded on the opposite coast of Ceylon in the Mahavamsa Ch. XXXI as having occurred in the reign of Kelani Tissa (cir. 200 BC) and which, according to the Rajavaliya, destroyed “100,000 large towns, 970 fishers’ villages and 400 villages inhabited by pearl fishers.” This may be deemed an exaggeration, but the Meridian of Lanka of the Indian Astronomer, which was reputed to pass through Ravana’s ancient capital in Ceylon, actually passes the Maldive Isles, quite 400 miles from the present western limit of Ceylon. An earlier submersion in the reign of Panduwasa (cir. 500 BC), is also recorded in the Rajāvaliya. Only the names of the poets of the first Academy and fragments of their works have come down to us, and one whole work of the second Academy composed in the earlier period, with extracts from a few works and the names of many others. The surviving work, Tolkappiyam, is a standard work on Grammar (a term covering a much wider range than in Western languages) and supplanted the Agastiyam, the grammar of the first Academy. The Tolkappiyam still holds a position of pre-eminent authority, and is of peculiar interest to the antiquarian and historian by reason of the light it throws on the customs and institutions of the ancient Tamil land. Many works of a high order of merit are extant of the third Academy, including the well-known Kural of Tiruvalluvar (which has been translated into many Western languages) and the poem Tiru-murukarrup-padai, a translation of which is given in this book.

The author Nakkirar lived about the first century, and was a member of the third Academy, which had its seat in the third Pandyan capital Madura, Ptolemy’s “royal Modoura of Pandion” and still an important religious literary and commercial centre. It was about this time that the first recorded embassy from the East reached imperial Rome. It came from a king of this line and is referred to by a contemporary writer Strabo (cir. 19 AD). In opening his account of India, he laments the scantiness of his materials and the lack of intercommunication between India and Rome; so few Greeks, and those but ignorant traders incapable of any just observation, had reached the Ganges, and from India but one embassy to Augustus, namely from one King Pandion or Porus had visited Europe (Geog. Indica XV, C.I. 73 et seq.). The name Porus was apparently a reminiscence from the expedition of Alexander the Great. The embassy to Augustus Suetonious attributes to the fame of his moderation and virtue, which allured Indians and Scythians to seek his alliance and that of the Roman people (Augustus, C. 21). Horace alludes to it in more than one ode. Addressing Augustus, he says, Te Cantaber non ante domabihis “The Spanish tribes, unused to yield, A similar reference is made in the Ode to Jupiter (Od. 1.12). The Tiru-murukARRup-paTai is a poem of the third Academy, and commences the anthology known as the Ten Lyrics (pattup pATTu) and is in praise of god Muruka. It belongs to a class of poems known in classic Tamil as ARRup paTai, literally “a guiding or conducting”, from aru, way, and paTutu, to cause. Various kinds of this class of poem are mentioned in the Tolkappiyam. A poet, musician, minstrel or dancer, on his way home with gifts from a patron, would direct others to him and make it the occasion f or singing his praise. Or, as in this poem, one who has received from his patron-god many precious spiritual boons tells others of his good fortune -- and how they too may win it. “If, striving for the wisdom that cometh of steadfastness in righteous deeds, thou with pure heart fixed upon His feet desirest to rest there in peace, then by that sweet yearning—the fruit of ancient deed—which spurneth all things else, thou wilt here now gain thy goal.” (vv. 62-68). This is the central idea of the poem. He is regarded as in his essence formless and beyond speech and thought, but assuming forms to suit the needs of his votaries and accepting their worship in whatever form, if only heartfelt. This is indeed the normal Hindu attitude in religious matters and accounts for its infinite tolerance. All regions are ways, short or long, to God. “The nameless, formless one we will call and worship by a thousand names in chant and dance,” the Psalmist Manikkavachakar cries. God, under whatever name or form sought, comes forward to meet the seeker and help his progress onwards through forms suitable to his development. “They who worship other gods with faith and devotion, they also worship me,” it is declared in the Bhagavad Gita (IX, 21). The merit claimed for the Hindu religious system is that it provides spiritual food and help for the soul in every stage of its development; hence it is significantly called the Ladder Way (Sopaana Maarga). The God Muruka has many shrines and modes of worship. Some of them are described in this poem, which thus serves, as its name indicates, as a “Guide to the Holy Muruka.” The shrines are all in Tamil land. The first shrine mentioned is Tirupparankunram, a hill about five miles southwest of Madura. “He dwelleth gladly on the Hill west of the Clustered Towers—gates rid of battle, for the foe hath been crushed and the ball and doll defiantly tied to the high flag-staff are still—faultless marts, Lakshmi’s seats, streets of palaces. “He dwelleth on the Hill where swarms of beauteous winged bees sleep on the rough stalks of lotuses in the broad stretches of muddy fields; they blow at dawn round the honey-dripping neytal blooms and with the rising sun sing in the sweet flowers of the pool as they open their eyes.” (vv. 67-77). The other shrines specifically named are Alaivai (‘wave mouth’ v. 125), now known as Tiruchendur, a shrine on the southern coast about 36 miles from Tinnevelly; Avinankudi (v.176), now known as Palani Malai (Palani Hills), about the same distance from Dindigul and a well-known hill station; Tiru-Erakam (v. 189), now called Swamimalai, a hill about four miles from Kumbakonam. Each of the shrines with its appropriate incidents and associations is the subject of a little picture-making a sort of cameo or gem strung together in this poem forming a perfect whole (vv. 1-77, 78-125, 126-176, 177-189). Three of the shrines are situated amid mountains and forests, for they are dear to Muruka. One section (vv. 190-217) describes his “Sport on the mountains” and another (v. 218 ad fin.) describes him as dwelling in “fruit groves” and worshipped by forest tribes. The shrine of Kataragama is understood to be included in the last. The poet enumerates many other places and ways in which the god manifests himself: festivals accompanied with goat sacrifices and frenzied dancers, groves and woods, rivers and lakes, islets, road-junctions, village-meetings, the kadamba tree (eugenia racemosa), etc., and lastly wherever votaries seek him in prayer (vv. 218-225), recalling Jesus’ saying (Matth. XVIII, 20) “where two or three are assembled in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” Muruka would thus appear to be a deity in whom were amalgamated many legends and traditions, many aspects of religion and modes of worship, primitive and advanced, and to embody the Hindu ideal of God immanent in all things and manifesting himself wherever sought with love. Muruka means tender age and beauty and is often represented as the type of perennial youth, sometimes as quite a child. There is in Vaithiswaran temple near Tanjore an exquisite figure of the child-god. He is also worshipped in the form of a six-faced god, the legendary origin of which form I have already given (pp. 115). Verses 90-118 describe the part played by each face and each of his twelve arms and show that this form was a personification of various divine aspects and powers. “One face spreadeth afar rays of light, perfectly lighting the world’s dense darkness; one face graciously seeketh his beloved and granteth their prayers; one face watcheth over the sacrificial rites of the peaceful ones who fail not in the way of the Scriptures; one face searcheth and pleasantly expoundeth hidden meanings, illumining every quarter like the moon; one face, with wrath mind filling, equality ceasing, wipeth away his foes and celebrateth the battle sacrifice; one face dwelleth smiling with slender waisted Vedda maid, pure-hearted Valli.” He is thus worshipped as the god of wisdom by those who seek spiritual enlightenment, as the god of sacrifice and, ritual by ritualists, as the god of learning by scholars, as the giver of all boons, worldly and spiritual, to his devotees. In punishing the Titans, his divine heart (according to the commentator) seemed for the moment to deviate from the feeling of equality towards all his creatures. But the punishment was really an expression of his fatherly love for his children. In the same way the wedding of Valli by the god was to set to mankind a pattern of family life and duty. End Notes[1] 29 miles from Hambantota, 87 from Badulla and 10-1/2 from the nearest post town Tissamaharama: situated on the left bank of the Menik Ganga, which rises in Maussagolla Estate, 13 miles from Badulla. [2] The fifteen other sacred places are: 1. Mahiyangana (Bintenne in Uva on the right bank of the Mahaweli Ganga), 2. Nagadipa (said to be in the Northern Province), 3. Kelaniya (near Colombo), 4. Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak), 5. Divaguha (perhaps the same as Bhagava Lena near Adam’s Peak), 6. Dighflvapi (Nakha Vihare in Batticaloa District near Sengapadi), 7. Mutiyangana (in Badulla town), 8. Tissamaharama (in Hambantota District) with the six following places in Anuradhapura city, 9. Mahabodhi, 10, Mirisvetiya, 11. Ruwanveliseya, 12. Thuparama, 13. Abhayagiri, 14. Jetavana, and lastly 15. Selacetiya (at Mihintale near Anuradhapura). [3] Ancumukan tOnRi lARumukan tOnRum [4] OrumurukAvenRennuLLankuLiravuvantuTanE [5] The Sanskrit epic Skanda Purana, which is said to contain a hundred thousand stanzas, has no existence in a collective form. Fragments in shape of sanhitas, kandhas, mahatmyas are found in various parts of India. The Tamil poem by Kachchiappa Swami of Kanchi is said to be based on the first six kandhas of the Sivarahasya Kandha, the first of twelve sections of the Sankara Mahatmya of the Sanskrit epic, and is a work of high literary merit, Wordsworthian in chaste, simplicity of style, but with an elevation and dignity rarely attained by him. [6] There is trace of an earlier God than Uranus in the Woodpecker God Picus. See Aristophanes, Birds, 645 et seq. [7] The instruction, extending over many pages, ends thus: “The venerable Sanatkumara showed to Narada, after his faults had been rubbed out, the other side of darkness. They, call Sanatkumara Skanda, yea, Skanda they call him.” [8] Vincent Smith, Early History of India, p. 271. [9] Extracts from the burglar’s soliloquy: “Here is a spot weakened by constant sun and sprinkling and eaten by saltpeter rot. And here is a pile of dirt thrown up by a mouse. Now Heaven be praised! My venture prospers. This is the first sign of success for Skanda’s sons. Now first of all, how shall I make the breach? The blessed Bearer of the Golden Lance has prescribed four varieties of breach (here follows their description and the choice). I will make that… Praise to the boon conferring God, to Skanda of immortal youth! Praise to him, the Bearer of the Golden Lance, the Brahmins’ God, the Pious! Praise to him, the Child of the Sun! Praise to him, the teacher of magic, whose first pupil I am! For he found pleasure in me and gave me magic ointment, With which so I anointed be, [10] Called Taraka by the Sanskrit poets, but Sura or Surapatuma by the Tamils, who give the name Taraka to a younger brother. [11] The peacock is therefore a sacred bird in India (as in Egypt and Greece)—a fact, the ignorance of which brings British sportsmen into collision with the people. [12] Perhaps I should say “Anacreontic”, for most of what has come down to us as “Anacreon” are imitations that bear in the dialect the treatment of Eros as a frivolous fat boy, the personifications, the descriptions of works of art the marks of a later age. [13] Yaazhpaana Vaipava Maalai (Brito. p. 11). [14] From Kandapuranam, CavaraNappaDalam, 20-21: “In Saravanai’s waters her child’s six forms she (Uma) lovingly clasped with both arms and lifted and of his six beauteous faces and twice six shoulders she made one form, she, the mistress of the triple world. As the diverse energies of our Father, at the involution of all things, become one as before, so the twelve forms of Gauri’s son became one and he received the name Kandan.” Uma is the consort of Siva and his inseparable energy (sakti), through whom alone He (regarded as the absolute) acts. Joined to Sakti, Siva becomes Sakta (i.e., able to act), without her he cannot even move, sings Sankaracharya in a famous hymn. [15] Kantazhi – oru paRRukkOTinRi aruvAkit tAnE niRkun tattuvankaTanta poruL (naccinArkkiniyar). [16] Like most Ceylon Kings, he was more of a Hindu than a Buddhist. An ancient MS account of Ridi Vihara, which he built and endowed, states that on the occasion of its consecration he was accompanied thither by 500 Bhikkus (Buddhist monks) and 1,500 Brahmins versed in the Vedas (See paper read at the R.A.S.B. in June, 1923 on “Palm Leaf MSS. in Ridi Vihara”). Throughout Ceylon history, the court religion was Hinduism, and its ritual and worship largely alloyed and affected the popular Buddhism and made it very unlike the religion of the Buddha. [17] He had for over a year been residing in Colombo in order to complete an elaborate trust deed in respect of the temples and lands in his charge. This deed he executed on 9th March, 1898 (No. 2317, J. Caderman, N.P.). Its preamble gives the history of his long connection with the temple and the nature of the succession from of old. [18] My grandfather A. Coomara Swami, Raja Vasal Mudaliyar, of the Governor’s Gate and member of the Legislative Council on its first establishment (representing there till his death the Tamils and Muhammadans of this Island), under the orders of the Governor and Commander-in-Chief General Brownrigg, escorted the King and his Queens to Colombo (then a very arduous journey) and had charge of the arrangements for their stay here and their embarkation for India. In the year 1890 at Tanjore, in the Madras Presidency, I had the honour of being presented to the last surviving queen of Kandy. In spite of very straitened circumstances, she maintained the traditions and ceremonial of a Court. Speaking from behind a curtain, she was pleased to welcome me and to express her appreciation of services rendered to her family since their downfall. A lineal descendant of the Kings of Ceylon held, till a few years ago, a clerkship in the Registrar-General’s department, a living testimony to the revolutions of the wheel of fortune.

[19] See also his petition to the Government Agent, Uva, 23rd August 1897, where most of the facts are recorded. I am indebted to the Government Agent, Uva, for access to the document. [20] Alutnuwara Deiyyo, represented in the procession, according to Knox, by a painted stick. [21] The Kataragam God and the Goddess Pattini. [22] Compare the mystic chest employed in the celebration of the mysteries of Dionysus. The AuthorSir Ponnambalam Arunachalam (1853-1924) was the first Ceylonese to join the Civil Service by open competitive examination; he was the first President of the Ceylon University Association, which campaigned for the establishment of a University in Ceylon, and the first President of the Ceylon National Congress, which for the first time brought together all communities in the Island to make a united demand from the British Government for swaraj or self rule. As the first President of the Social Service League and the Ceylon Workers' Welfare League, he led the movement for social justice to underprivileged sections of the community. The author of many scholarly writings on law, history, religion and philosophy, he was also the first Ceylonese President of the Royal Asiatic Society (Ceylon Branch).

|

![Pal Kudi Bawa [14 kb]](../pix/palkudi.jpg)